ALASKAN, ALEX CAN, AL ASKIN’

July 26, 1998: On the fringe of the Alaska Interior and then, before and after, in the heart of the Mojave Desert.

In Fairbanks Territory

I am three weeks into a five-week work tour, stationed in Fairbanks, Alaska, as part of a two-man Lockheed Martin field crew contracted by the federal government to sample creeks running through placer gold mine claims to test for trace metals contamination on the hem of the outskirts of the so-called "Last Frontier." With the day off and authorized to have use of the company-leased rental car during work breaks--provided I buy the gas--I begin a drive down the George Parks Highway (a.k.a. AK-3) from Fairbanks toward Anchorage for some sightseeing; but primarily to attempt to track down any hitchhiker graffiti written along it.

Uncharacteristically for me in the pursuit of thumber writings, I am pessimistic about finding any inscriptions this time out. This stems from my earlier searches throughout the greater Fairbanks area during my stay here, where I have come up with not one message. This is in stark contrast to my being filled with hope that I would be filling several logbook pages with scores of inscriptions, since I had predicted that Alaska would have more than its share of hitchhikers buzzing in, out, around, and through it over the years; many of whom must surely would have passed through Fairbanks. That’s because Fairbanks, which is not only a pleasant town and a travel destination unto itself--at least in the summer--it is also an overland hub and crossroads from which radiates both paved and well-groomed unpaved arterials north to Prudhoe Bay, east to the banks of the Yukon River, south to Anchorage, and southeast toward Canada and the Alcan Highway to what Alaskans call “outside” or “the other (or lower) 48."

These roads, when they meet, form a loose, seemingly haphazardly constructed beltway defining the margins of central Fairbanks. They bear the names of Richardson, for Major Wilds P. Richardson; Steese, for General James Steese; Mitchell, for Lieutenant Robert J. Mitchell; Johansen, for rail or road engineer Woodrow Johansen; and the road down which I was traveling that day, George Parks, for the one-time governor of Alaska. All prominent contributors to the development of the state and certainly substantial individuals in their own respective rights, the highways and expressways named for these gents collectively, connectively, and crossroads-wise seem to form more of a set of sagging braces fastened to the work-worn britches of this most-times icy berg, rather than a belt wrapping its way around it. Loose-cinched suspenders seem more fitting, anyway, for the relative freedom from constrictions typically associated with the image that is the “Alaska state of mind” or “the state Alaskans have in mind."

This amalgam of roads frames the low, boxy skyline of this high-latitude city; a view composed of an uninspiring hodgepodge of structures that gives the impression the place was designed by a collective of apathetic architects funded by bottom-line bureaucrats, resulting in conglomerate of buildings cobbled together in a style that might be termed municipal-military, cubical-conformist, or simply basic blah---save, of course for the few rustic older buildings huddled around its historic downtown. Thus, it is easy to see why, at least on its surface, folks in Anchorage--its order-of-magnitude, lower-in-latitude subarctic neighbor 300 miles distant--mockingly call Fairbanks “Squarebanks.” Not to be outdone, Farbanksans counter with a salvo to their surficially self-confident, quasi-cosmopolitan Alaskan brethren, mockingly referring to the big city as “Los Anchorage.”

Nondescript skyline aside, what surprises me about all these impressively named roads spinning into, out of, and around Fairbanks--clutching hold of each other like the hands in the Oppenheimer Fund logo--was the complete absence of hitchhiker graffiti along them. (It may be appropriate here to point out that the logo for the Oppenheimer mutual fund, with each of its four hands grasping hold of the wrist perpendicular to the other, shows all fingers, but no thumbs!) This absence of thumber inscriptions is especially surprising, considering the vastness of Alaska and the few other auto routes down which to drive or on which to flag rides other than the aforementioned roads beginning in, ending at, or bending through Fairbanks. I speculate as to why there are no graffiti in and around this Alaskan crossroads; that perhaps the extreme weather conditions has worn the writings away, or maybe the roads and poles and road signs are all fairly new, or something else I just cannot put my finger on–or press my thumb atop.

Into the Wild Ride

In any event, as I drive south down “The Parks” this fair day, I am anything but encouraged about coming upon any messages along it. But, hell, I am in Alaska. Neither tourist nor tenant nor tramp am I. And come what may, I am basking in the glory of the moment!

Apart from the graffiti search, another goal for me this day is to get at least as far as Denali National Park, which lies down and whose mass rises halfway to the sky about halfway between the two largest of Alaska’s cities. Along the way, I half-heartedly half-check some of the most likely light poles and road signs dotting the shoulder of the mostly two-lane Parks Highway as I pass such world-renown places as Skinny Dick’s Halfway Inn--an area landmark roadhouse whose fame, no doubt, in large part comes from its name. It sits (stands? was erected?) half way between Fairbanks and the small fishing village of Nenana. Nenana is, itself, a place of international acclaim--not for its name, but for taking two-dollar bets on melting ice–specifically, in the Nenana Ice Classic; where people throughout the world participate in an annual pool by predicting the exact date, hour, and minute the numbing near-Arctic Circle cold which forms the ice on the adjacent Tanana River gives up its frigid grip to the soothing warmth and thawing of spring to the point that a black-and-white striped tripod set in the middle of the frozen river by the Nenana townsfolk breaks through. And, at two bucks a pop, the person with the closest guess takes the pot–neither a bet covered by the odds makers in Vegas nor a staged show ever performed on the Las Vegas Strip.

In Fairbanks Territory

I am three weeks into a five-week work tour, stationed in Fairbanks, Alaska, as part of a two-man Lockheed Martin field crew contracted by the federal government to sample creeks running through placer gold mine claims to test for trace metals contamination on the hem of the outskirts of the so-called "Last Frontier." With the day off and authorized to have use of the company-leased rental car during work breaks--provided I buy the gas--I begin a drive down the George Parks Highway (a.k.a. AK-3) from Fairbanks toward Anchorage for some sightseeing; but primarily to attempt to track down any hitchhiker graffiti written along it.

Uncharacteristically for me in the pursuit of thumber writings, I am pessimistic about finding any inscriptions this time out. This stems from my earlier searches throughout the greater Fairbanks area during my stay here, where I have come up with not one message. This is in stark contrast to my being filled with hope that I would be filling several logbook pages with scores of inscriptions, since I had predicted that Alaska would have more than its share of hitchhikers buzzing in, out, around, and through it over the years; many of whom must surely would have passed through Fairbanks. That’s because Fairbanks, which is not only a pleasant town and a travel destination unto itself--at least in the summer--it is also an overland hub and crossroads from which radiates both paved and well-groomed unpaved arterials north to Prudhoe Bay, east to the banks of the Yukon River, south to Anchorage, and southeast toward Canada and the Alcan Highway to what Alaskans call “outside” or “the other (or lower) 48."

These roads, when they meet, form a loose, seemingly haphazardly constructed beltway defining the margins of central Fairbanks. They bear the names of Richardson, for Major Wilds P. Richardson; Steese, for General James Steese; Mitchell, for Lieutenant Robert J. Mitchell; Johansen, for rail or road engineer Woodrow Johansen; and the road down which I was traveling that day, George Parks, for the one-time governor of Alaska. All prominent contributors to the development of the state and certainly substantial individuals in their own respective rights, the highways and expressways named for these gents collectively, connectively, and crossroads-wise seem to form more of a set of sagging braces fastened to the work-worn britches of this most-times icy berg, rather than a belt wrapping its way around it. Loose-cinched suspenders seem more fitting, anyway, for the relative freedom from constrictions typically associated with the image that is the “Alaska state of mind” or “the state Alaskans have in mind."

This amalgam of roads frames the low, boxy skyline of this high-latitude city; a view composed of an uninspiring hodgepodge of structures that gives the impression the place was designed by a collective of apathetic architects funded by bottom-line bureaucrats, resulting in conglomerate of buildings cobbled together in a style that might be termed municipal-military, cubical-conformist, or simply basic blah---save, of course for the few rustic older buildings huddled around its historic downtown. Thus, it is easy to see why, at least on its surface, folks in Anchorage--its order-of-magnitude, lower-in-latitude subarctic neighbor 300 miles distant--mockingly call Fairbanks “Squarebanks.” Not to be outdone, Farbanksans counter with a salvo to their surficially self-confident, quasi-cosmopolitan Alaskan brethren, mockingly referring to the big city as “Los Anchorage.”

Nondescript skyline aside, what surprises me about all these impressively named roads spinning into, out of, and around Fairbanks--clutching hold of each other like the hands in the Oppenheimer Fund logo--was the complete absence of hitchhiker graffiti along them. (It may be appropriate here to point out that the logo for the Oppenheimer mutual fund, with each of its four hands grasping hold of the wrist perpendicular to the other, shows all fingers, but no thumbs!) This absence of thumber inscriptions is especially surprising, considering the vastness of Alaska and the few other auto routes down which to drive or on which to flag rides other than the aforementioned roads beginning in, ending at, or bending through Fairbanks. I speculate as to why there are no graffiti in and around this Alaskan crossroads; that perhaps the extreme weather conditions has worn the writings away, or maybe the roads and poles and road signs are all fairly new, or something else I just cannot put my finger on–or press my thumb atop.

Into the Wild Ride

In any event, as I drive south down “The Parks” this fair day, I am anything but encouraged about coming upon any messages along it. But, hell, I am in Alaska. Neither tourist nor tenant nor tramp am I. And come what may, I am basking in the glory of the moment!

Apart from the graffiti search, another goal for me this day is to get at least as far as Denali National Park, which lies down and whose mass rises halfway to the sky about halfway between the two largest of Alaska’s cities. Along the way, I half-heartedly half-check some of the most likely light poles and road signs dotting the shoulder of the mostly two-lane Parks Highway as I pass such world-renown places as Skinny Dick’s Halfway Inn--an area landmark roadhouse whose fame, no doubt, in large part comes from its name. It sits (stands? was erected?) half way between Fairbanks and the small fishing village of Nenana. Nenana is, itself, a place of international acclaim--not for its name, but for taking two-dollar bets on melting ice–specifically, in the Nenana Ice Classic; where people throughout the world participate in an annual pool by predicting the exact date, hour, and minute the numbing near-Arctic Circle cold which forms the ice on the adjacent Tanana River gives up its frigid grip to the soothing warmth and thawing of spring to the point that a black-and-white striped tripod set in the middle of the frozen river by the Nenana townsfolk breaks through. And, at two bucks a pop, the person with the closest guess takes the pot–neither a bet covered by the odds makers in Vegas nor a staged show ever performed on the Las Vegas Strip.

A third and as equally compelling quest for my road trip this day–in addition to reaching Denali National Park and seeking roadside graffiti--is to find the dirt road called Stampede Trail. It was down this unimproved spur that juts into the wilderness from the Parks Highway just north of Healy--a coal mining town just north of the Denali park entrance–that six years pior, in 1992, a young, optimistic, and some say idealistic and reckless adventurer named Chris McCandless would walk and, for better or worse, forever infuse himself into the lore of Alaska; trekking into the wild from which he never would return alive. His lifeless body was found in the rusting corpse of Fairbanks City Bus #142, a dilapidated shell in a state of arrested decay which had been dragged out there years or decades before by a mining company intended as a bunkhouse for its workers. And had since been used as a shelter by hunters and anyone else who ambled or otherwise made the twenty-five or so miles down Stampede Trail to find the bus at its last stop out there on the edge of the shadows of Mt. McKinley.

Chris McCandless, it is a known fact, was at least one soul who at one time hitchhiked into and through Alaska. I can say this, not because of any graffiti I read along its roads--since I at this point have found not a scribble by anyone--but rather because this is documented in Into the Wild (Jon Krakauer, Random House Publishing Group, 1996), a book I began reading at the coaxing of my teenaged nephew, Brad, just before leaving for this own trip to Alaska and which I finished on the long plane flight from Las Vegas up to Fairbanks. The book achronologically chronicles in detail, the true story of a near-two-year stretch of the travels and sojourns of young McCandless inside Alaska at its end and “outside” before that. So, on this day, being that I am in and around some of the very same areas the book describes McCandless as having visited, slept in, and passed through, I am compelled by curiosity to come face-to-face with some of these very same places. And as I do, I wonder if I am somehow being affected by them, especially with the vivid images described in the book still very much fresh on my mind.

Chris McCandless, it is a known fact, was at least one soul who at one time hitchhiked into and through Alaska. I can say this, not because of any graffiti I read along its roads--since I at this point have found not a scribble by anyone--but rather because this is documented in Into the Wild (Jon Krakauer, Random House Publishing Group, 1996), a book I began reading at the coaxing of my teenaged nephew, Brad, just before leaving for this own trip to Alaska and which I finished on the long plane flight from Las Vegas up to Fairbanks. The book achronologically chronicles in detail, the true story of a near-two-year stretch of the travels and sojourns of young McCandless inside Alaska at its end and “outside” before that. So, on this day, being that I am in and around some of the very same areas the book describes McCandless as having visited, slept in, and passed through, I am compelled by curiosity to come face-to-face with some of these very same places. And as I do, I wonder if I am somehow being affected by them, especially with the vivid images described in the book still very much fresh on my mind.

The Northern Lights Meet the Neon (or the aurora borealis meets the aura of Las Vegas)

Aside from his wilderness extended stay and literal dead-ending in Alaska, there is much else written about McCandless with respect to his brief, but intensively colorful hitchhiking “career,” which began in July of 1990 but a raven’s glide from Las Vegas, Nevada--a place which, in polar opposition to Nenana, is famous for taking hot bets from high rollers and where the only ice to be found is crushed and cubed and used to keep drinks cold and bettors numb to thaw only their inhibitions to bring on a free flow of cash. It was under the blazing 1990 midsummer midday Mojave Desert sun with his car stuck dead in an arroyo after taking on flash-flood waters from a thunderstorm the afternoon before--not a sliver or cube of ice for miles--that a stranded, desperate, and ill-prepared Chris McCandless managed to stagger to the coarse, gravelly shoreline on the Arizona side of Lake Mead. There he would flag down a passing boat and be transported across to the Nevada side of this vast man-made desert lake and be dropped on the docks of the Callville Bay Marina.

The village of Callville, for which the bay and its marina are named, is today a place primarily relegated to the annals of history, most notably because of the exploits of an earlier American explorer. For it was there in 1869, on what was at the time the west bank of the Colorado River, where John Wesley Powell and his party of discovery--battered and drawn after surviving the amazing journey as the first known humans to boat through the Grand Canyon--mercifully would land and recuperate. Ironically, although Powell and his crew avoided drowning in the

Colorado, the village of Callville would itself be swallowed up by the very same river waters several decades later when the construction of Hoover Dam farther downstream created Lake Mead behind it. Other than in history books and the fading memories of a few old timers, what remains of the village of Callville above the waterline is the bay that formed into the hills surrounding the now submerged town, and the marina subsequently built and floating above it. And, while this place is near to where the Powell expedition concluded, it is also the point at which the hitchhiking McCandless party of one commenced. This all comes back around to Alaska, at least within the realm of my own experience. Coincidentally–or maybe otherwise--in the spring of 2004, during the rewriting and editing of this essay and while still working for Lockheed Martin, the same company that had sent me into the Alaska Interior eight years prior, I was involved in another field research project that took me to a gasoline underground storage tank spill in the parking lot of the very same Callville Bay Marina where, in July of 1990, Chris McCandless came ashore.

So, it was at this marina and on the winding, dusty road leading out from it that the carless, some may say careless, but evidently fearless McCandless bummed his first land ride to begin an odyssey which would two years later bring him to turn from the Parks Highway to be let off and land him on Stampede Trail. And, it was his tale and my job that, eight years later, brings me here, as well.

Now, it was in the middle of his two-year journey--for about three month period in early 1991–that McCandless, after traveling hither and yon throughout the western United States, would go back to southern Nevada and live on the streets of Las Vegas with folks he came to call “tramps, bums, and winos.” Presumably, these were terms of great affection rather than affliction but, perhaps, some affiliation if he cared to admit it or not. During that time, he worked for a while at an unnamed Italian restaurant.

A bottle of white, a bottle of red

Perhaps a bottle of rose instead

We'll get a table near the street

In our old familiar place

You and I, face to face.

A bottle of red, a bottle of white

It all depends upon your appetite

I'll meet you any time you want

In our Italian Restaurant.

--Scenes From An Italian Restaurant, Stranger, Billy Joel, ©1977

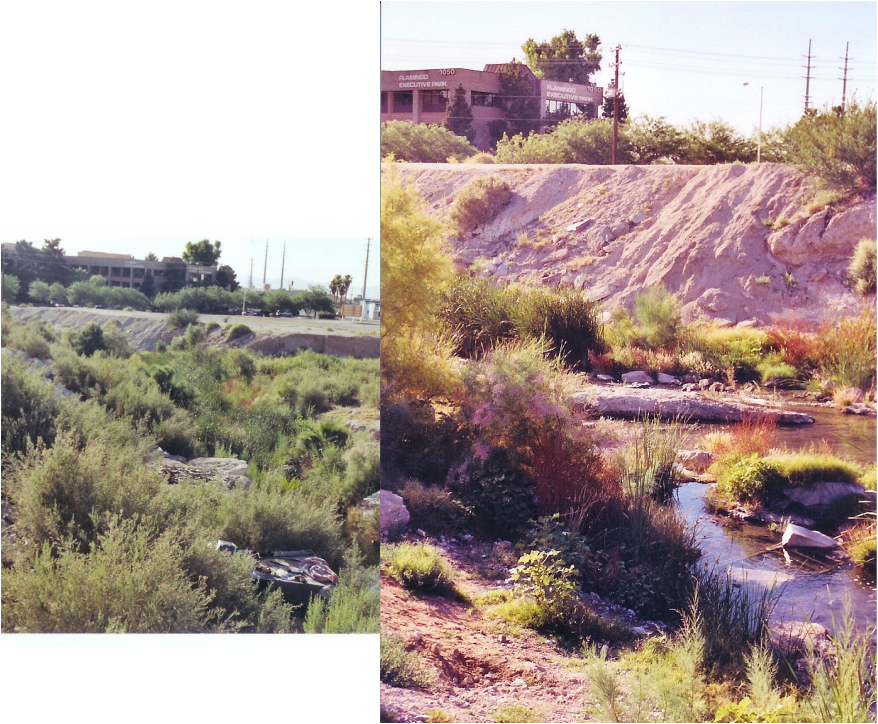

Now, in Las Vegas, Nevada--a place where over the last couple of decades I have fathered and raised my children, forged a career, and found a home--homeless guys for at least that long a time have been quietly and innocuously squatting in camps on the sandy ledges and under the caliche overhangs at the confluence of the Tropicana Wash and Flamingo Wash in an undeveloped piece of desert encircled by urban commercial building, strip malls, and low-income apartments not far to the east of the looming resorts on the Las Vegas Strip. Part of a natural drainage system within the Las Vegas Valley which nowadays collects a steady trickle of an unnatural soup of the city’s landscaping runoff and channels the occasional violent summer flash-flood deluges toward Lake Mead--of the kind that disabled Chris McCandless’s car in Arizona--these arroyos support dense stands of native cattails, billows of invasive salt cedar, and the occasional fugitive Mexican fan palm. The shade from this rich riparian community provides relief and cover for the semi-transient occupants of these illegal encampments. Their presence, surprisingly, is tolerated by the local police in a town whose law enforcement professionals are not especially noted for their tolerance. Curiously, the word nenana is Athabascan for “a good place to camp between the rivers.” Now, while this likely specifically refers to the place at the confluence of the Tanana and Nenana rivers of Alaska where the village of Nenana sits, perhaps this Nevada location between two quasi-ephemeral desert water courses which also happens to be a good place for some to camp, could be called a Las Vegas nenana.

[Author's Note: Since the original writing of this essay, this confluence of the Flamingo and Tropicana washes has been channelized, box-culverted, and paved over; although, this does not necessarily preclude some homeless folks from continuing to reside therein, there-under, or thereabouts.]

Aside from his wilderness extended stay and literal dead-ending in Alaska, there is much else written about McCandless with respect to his brief, but intensively colorful hitchhiking “career,” which began in July of 1990 but a raven’s glide from Las Vegas, Nevada--a place which, in polar opposition to Nenana, is famous for taking hot bets from high rollers and where the only ice to be found is crushed and cubed and used to keep drinks cold and bettors numb to thaw only their inhibitions to bring on a free flow of cash. It was under the blazing 1990 midsummer midday Mojave Desert sun with his car stuck dead in an arroyo after taking on flash-flood waters from a thunderstorm the afternoon before--not a sliver or cube of ice for miles--that a stranded, desperate, and ill-prepared Chris McCandless managed to stagger to the coarse, gravelly shoreline on the Arizona side of Lake Mead. There he would flag down a passing boat and be transported across to the Nevada side of this vast man-made desert lake and be dropped on the docks of the Callville Bay Marina.

The village of Callville, for which the bay and its marina are named, is today a place primarily relegated to the annals of history, most notably because of the exploits of an earlier American explorer. For it was there in 1869, on what was at the time the west bank of the Colorado River, where John Wesley Powell and his party of discovery--battered and drawn after surviving the amazing journey as the first known humans to boat through the Grand Canyon--mercifully would land and recuperate. Ironically, although Powell and his crew avoided drowning in the

Colorado, the village of Callville would itself be swallowed up by the very same river waters several decades later when the construction of Hoover Dam farther downstream created Lake Mead behind it. Other than in history books and the fading memories of a few old timers, what remains of the village of Callville above the waterline is the bay that formed into the hills surrounding the now submerged town, and the marina subsequently built and floating above it. And, while this place is near to where the Powell expedition concluded, it is also the point at which the hitchhiking McCandless party of one commenced. This all comes back around to Alaska, at least within the realm of my own experience. Coincidentally–or maybe otherwise--in the spring of 2004, during the rewriting and editing of this essay and while still working for Lockheed Martin, the same company that had sent me into the Alaska Interior eight years prior, I was involved in another field research project that took me to a gasoline underground storage tank spill in the parking lot of the very same Callville Bay Marina where, in July of 1990, Chris McCandless came ashore.

So, it was at this marina and on the winding, dusty road leading out from it that the carless, some may say careless, but evidently fearless McCandless bummed his first land ride to begin an odyssey which would two years later bring him to turn from the Parks Highway to be let off and land him on Stampede Trail. And, it was his tale and my job that, eight years later, brings me here, as well.

Now, it was in the middle of his two-year journey--for about three month period in early 1991–that McCandless, after traveling hither and yon throughout the western United States, would go back to southern Nevada and live on the streets of Las Vegas with folks he came to call “tramps, bums, and winos.” Presumably, these were terms of great affection rather than affliction but, perhaps, some affiliation if he cared to admit it or not. During that time, he worked for a while at an unnamed Italian restaurant.

A bottle of white, a bottle of red

Perhaps a bottle of rose instead

We'll get a table near the street

In our old familiar place

You and I, face to face.

A bottle of red, a bottle of white

It all depends upon your appetite

I'll meet you any time you want

In our Italian Restaurant.

--Scenes From An Italian Restaurant, Stranger, Billy Joel, ©1977

Now, in Las Vegas, Nevada--a place where over the last couple of decades I have fathered and raised my children, forged a career, and found a home--homeless guys for at least that long a time have been quietly and innocuously squatting in camps on the sandy ledges and under the caliche overhangs at the confluence of the Tropicana Wash and Flamingo Wash in an undeveloped piece of desert encircled by urban commercial building, strip malls, and low-income apartments not far to the east of the looming resorts on the Las Vegas Strip. Part of a natural drainage system within the Las Vegas Valley which nowadays collects a steady trickle of an unnatural soup of the city’s landscaping runoff and channels the occasional violent summer flash-flood deluges toward Lake Mead--of the kind that disabled Chris McCandless’s car in Arizona--these arroyos support dense stands of native cattails, billows of invasive salt cedar, and the occasional fugitive Mexican fan palm. The shade from this rich riparian community provides relief and cover for the semi-transient occupants of these illegal encampments. Their presence, surprisingly, is tolerated by the local police in a town whose law enforcement professionals are not especially noted for their tolerance. Curiously, the word nenana is Athabascan for “a good place to camp between the rivers.” Now, while this likely specifically refers to the place at the confluence of the Tanana and Nenana rivers of Alaska where the village of Nenana sits, perhaps this Nevada location between two quasi-ephemeral desert water courses which also happens to be a good place for some to camp, could be called a Las Vegas nenana.

[Author's Note: Since the original writing of this essay, this confluence of the Flamingo and Tropicana washes has been channelized, box-culverted, and paved over; although, this does not necessarily preclude some homeless folks from continuing to reside therein, there-under, or thereabouts.]

In any event, there is a stretch of the Flamingo Wash only several dozen yards downstream from where its merge with the Tropicana, which is bordered in a ten-foot-high curtain of oleanders woven through an eight-foot-high chain-link fence. This row of green bespeckled with flowers white and pink runs behind a three-story commercial office building called the Flamingo Executive Park. Called “FEP,” for short, by its tenants, which are comprised of an eclectic assortment of companies, including the small Lockheed Martin satellite office I have worked in for much of the time I have lived in Las Vegas. For the record, this office building has neither a park, nor flamingos, nor, judging by most of the cars parked in the lot, much in the way of executives on the premises, either. One thing it does have, though, is a nice-sized bathroom just off its airy water-featured, ficus-fringed, sky-lighted lobby atrium. And some of those very same guys camped upstream down in the wash out back would every so often emerge one or two at a time and make use the facilities to spruce up and perform other various acts of personal hygiene of the Greyhound bus depot variety--not that there's anything wrong with that.

She said, “I'm gonna' hire a wino, to decorate our home,

So you can feel more at ease here, and you won't have to roam.

When you and your friends get off from work, and have a powerful thirst.

There won't be any reason, why you can't stop off here first.”

--I'm Gonna Hire A Wino (To Decorate Our Home), "2001", © Dewayne Blackwell, 2001, Nashville

Now, those very same few months Chris McCandless was holed up in Las Vegas, I was working for Lockheed Martin out of offices in FEP. Therefore, it is plausible--although admittedly much more as a thesis than a theorem--that while in living in Vegas, McCandless may have (1) hooked up with one or some of these very same homeless “tramps, bums, and winos” camped down in the Flamingo Wash behind FEP, (2) at one time or another camped down there with them, and (3) used the very same bathroom at FEP I have been known to visit with some degree of regularity during the course of a given work day. If this is all so, then it would not be beyond the pale to submit that (4) he and I may have crossed paths with or passed water right beside each other right there in bathroom in FEP.

Irrespective of whether proofs to this theorem can ever be validated, and/or wherever in town it was he sought and found refuge, McCandless both before and following his stay in Las Vegas hitchhiked extensively into and out of the deserts of the southwest and up and down the California coast. In fact, after one of these hitches, after being dropped off on I-40 in Needles, California, and walking the dozen or so miles east along the interstate to the small Colorado River town of Topock, Arizona, he wound up buying himself a used canoe. With that, and a sack of rice and whatever he had in his pack, McCandless proceeded to launch the craft and paddle his way down through the lower reaches of the same river Powell and his expedition had once explored–granted the waters were far more tame and far less treacherous than those Powell and his men encountered. To the contrary, after passing Ehrenberg, Arizona, on his left and Blythe, Arizona, on his right and then through Yuma, he eventually crossed south of the border where he entered a dizzying, claustrophobic maze of tall reeds and the torturous flats of mud and silt that choke the delta separating Baja California from the rest of Mexico. Thus, crossing illegally into Mexico, I suppose he could derogatorilly have been termed a “muckback.” In any case, with help from some locals, he managed to get himself and his canoe out of the mire and into the salty, turbulent surf of the Sea of Cortez.

Several months and tens of degrees higher in latitude later in his journey, on his final hitchhike in April of 1992, just as the Tanana ice was breaking up and its meltwaters flowed past the confluence with the Nenana on its journey toward the Yukon River, and that year’s Ice Classic winner was raking in the pot, Chris McCandless, who by that time had acquired for himself the pseudonym, nom de plume, and alias of Alexander Supertramp, flagged a ride down The Parks in a pickup by Jim Gallien, an electrician on his way from Fairbanks to Anchorage. The following passage from Into the Wild provides a backdrop and recounts the events as they happened just south of Nenana, moments before Gallien turned down Stampede Trail to drop his rider off on the edge of his destiny:

"A hundred miles out of Fairbanks the highway begins to climb into the foothills of the Alaska Range. As the truck lurched over a bridge across the Nenana River, Alex looked down at the swift current and remarked that he was afraid of the water. "A year ago down in Mexico," he told Gallien, "I was out on the ocean in a canoe, and I almost drowned when a storm came up."'

Because McCandless was an avid journal writer, this allowed author Krakauer to so well catalogue much of his whereabouts in Into the Wild. But, who’s to say whether McCandless did not also write on a random freeway light pole or two while out thumbing rides on many of the same roads throughout the southwestern US I have been down while collecting my logbooksful of hitchhiker messages? Whether I have unknowingly come upon one or two, or if they are still out there somewhere waiting to be revealed, I cannot say. At least not so far.

What can be said for sure about all this is that, as it turns out, in mid-August 1992, the same week I began into the wild ride of my own of seeking hitchhiker graffiti, Chris McCandless’s journey would end in Fairbanks City Bus #142 from starvation. And it also turns out that it was a combination of my job and my hitchhiking research that led me to the exact two points at which McCandless got his first and left his last ride thumbing: Callville Bay Marina, Nevada, and Stampede Trail, Alaska.

Into the Wild came out in late 1996. By the time I found myself standing up there on Stampede Trail in midsummer of 1998, Chris McCandless’s name and his actions were still stirring deep emotional responses from many Alaskans, natives and transplants, alike. In fact, it seemed that not one of them didn’t have some opinion about him and his Alaska antics. It was as if a line was drawn in the snow between the two main camps pitched on his memory. One was of the mind that he was just another greenhorn–what Alaskans call a cheechacko–who came north and was unprepared and overconfident for the trials and tests he encountered, and that his idiocy and story wasn’t worth the ink and paper to print it on, nor time to write, read, and discuss it. But written, printed, read, and discussed it very much was.

On the other side of the opinion line were those who thought he was no different than most anybody else who came to Alaska for the first time, braced for the challenges it offered, but without a full grasp and complete understanding of the place. They would argue in his defense that, besides, he did last a whole four months or more out/in there, and he did it alone! Thus, the question was rhetorically posed, asking who among the native and one-time cheechacko critics, alike, could have stuck it out solo as long as McCandless did, anyway? He had guts and conviction, maybe more than sense. But, maybe all he needed was just a little more luck, be it the Las Vegas or Nenana or some other kind. And if he had, and walked out, would his antics and trail and tributaries have otherwise been so well remembered?

Irrespective of which side of the snow line they may have stood, there was no denying the compelling nature of this debate both inside and outside the state. This is evidenced by the fact that, since the publishing of Into the Wild, and likely because of it, there has been a Midwestern band which has taken on the name Fairbanks 142, after the bus that would be the last home and first last resting place if this adventurer. And, at least one song has been written and recorded honoring his trip and his spirit: The Ballad of Chris McCandless (Ellis Paul, 2002, Speed of Trees).

It’s a strange situation,

A wild occupation

Livin' my life like a song

–The Wino and I Know, Jimmy Buffet, Living and Dying In 3/4 Time, © 1974

So, depending on who you might ask and where you might ask it, McCandless either was a foolish fuck-head or is a fledgling folk hero. As with many controversial figures, the truth about him, the reality of his exploits, and the meaning of the last two years and the final few days and hours of his life likely has him fall somewhere between being a fool and hearty.

I drive west down Stampede Trail where, over the eight miles to the appropriately dubbed Eightmile Lake, the road turns from graded gravel to packed dirt to moist tracks to ponding ruts to mostly muck and approaching muskeg, at which point it became completely impassable for the passenger car I was pushing down it. Getting out with tall grasses and subarctic scrub doing their best to envelop and reclaim the road, I gaze out farther to the west in what I figure to be the general direction of where that derelict Bus #142 still rests and rusts. I think of Chris McCandless for a long moment. What crosses my mind are some of the chancy things I have done in all of my, to this point, 42 years. And with respect to the act of universal hitchhiking, isn't 42 the answer, anyway?

It leads me to wonder for both he and me: What if? What if I had rolled snake eyes somewhere along the way? And, what if he had not? How would my life have been summed up if I had? And, how might his be developing if he was still alive? I then snap a couple of pictures, take a deep breath of fireweed perfume, and go on my way satisfied at having faced the place he faced.

She said, “I'm gonna' hire a wino, to decorate our home,

So you can feel more at ease here, and you won't have to roam.

When you and your friends get off from work, and have a powerful thirst.

There won't be any reason, why you can't stop off here first.”

--I'm Gonna Hire A Wino (To Decorate Our Home), "2001", © Dewayne Blackwell, 2001, Nashville

Now, those very same few months Chris McCandless was holed up in Las Vegas, I was working for Lockheed Martin out of offices in FEP. Therefore, it is plausible--although admittedly much more as a thesis than a theorem--that while in living in Vegas, McCandless may have (1) hooked up with one or some of these very same homeless “tramps, bums, and winos” camped down in the Flamingo Wash behind FEP, (2) at one time or another camped down there with them, and (3) used the very same bathroom at FEP I have been known to visit with some degree of regularity during the course of a given work day. If this is all so, then it would not be beyond the pale to submit that (4) he and I may have crossed paths with or passed water right beside each other right there in bathroom in FEP.

Irrespective of whether proofs to this theorem can ever be validated, and/or wherever in town it was he sought and found refuge, McCandless both before and following his stay in Las Vegas hitchhiked extensively into and out of the deserts of the southwest and up and down the California coast. In fact, after one of these hitches, after being dropped off on I-40 in Needles, California, and walking the dozen or so miles east along the interstate to the small Colorado River town of Topock, Arizona, he wound up buying himself a used canoe. With that, and a sack of rice and whatever he had in his pack, McCandless proceeded to launch the craft and paddle his way down through the lower reaches of the same river Powell and his expedition had once explored–granted the waters were far more tame and far less treacherous than those Powell and his men encountered. To the contrary, after passing Ehrenberg, Arizona, on his left and Blythe, Arizona, on his right and then through Yuma, he eventually crossed south of the border where he entered a dizzying, claustrophobic maze of tall reeds and the torturous flats of mud and silt that choke the delta separating Baja California from the rest of Mexico. Thus, crossing illegally into Mexico, I suppose he could derogatorilly have been termed a “muckback.” In any case, with help from some locals, he managed to get himself and his canoe out of the mire and into the salty, turbulent surf of the Sea of Cortez.

Several months and tens of degrees higher in latitude later in his journey, on his final hitchhike in April of 1992, just as the Tanana ice was breaking up and its meltwaters flowed past the confluence with the Nenana on its journey toward the Yukon River, and that year’s Ice Classic winner was raking in the pot, Chris McCandless, who by that time had acquired for himself the pseudonym, nom de plume, and alias of Alexander Supertramp, flagged a ride down The Parks in a pickup by Jim Gallien, an electrician on his way from Fairbanks to Anchorage. The following passage from Into the Wild provides a backdrop and recounts the events as they happened just south of Nenana, moments before Gallien turned down Stampede Trail to drop his rider off on the edge of his destiny:

"A hundred miles out of Fairbanks the highway begins to climb into the foothills of the Alaska Range. As the truck lurched over a bridge across the Nenana River, Alex looked down at the swift current and remarked that he was afraid of the water. "A year ago down in Mexico," he told Gallien, "I was out on the ocean in a canoe, and I almost drowned when a storm came up."'

Because McCandless was an avid journal writer, this allowed author Krakauer to so well catalogue much of his whereabouts in Into the Wild. But, who’s to say whether McCandless did not also write on a random freeway light pole or two while out thumbing rides on many of the same roads throughout the southwestern US I have been down while collecting my logbooksful of hitchhiker messages? Whether I have unknowingly come upon one or two, or if they are still out there somewhere waiting to be revealed, I cannot say. At least not so far.

What can be said for sure about all this is that, as it turns out, in mid-August 1992, the same week I began into the wild ride of my own of seeking hitchhiker graffiti, Chris McCandless’s journey would end in Fairbanks City Bus #142 from starvation. And it also turns out that it was a combination of my job and my hitchhiking research that led me to the exact two points at which McCandless got his first and left his last ride thumbing: Callville Bay Marina, Nevada, and Stampede Trail, Alaska.

Into the Wild came out in late 1996. By the time I found myself standing up there on Stampede Trail in midsummer of 1998, Chris McCandless’s name and his actions were still stirring deep emotional responses from many Alaskans, natives and transplants, alike. In fact, it seemed that not one of them didn’t have some opinion about him and his Alaska antics. It was as if a line was drawn in the snow between the two main camps pitched on his memory. One was of the mind that he was just another greenhorn–what Alaskans call a cheechacko–who came north and was unprepared and overconfident for the trials and tests he encountered, and that his idiocy and story wasn’t worth the ink and paper to print it on, nor time to write, read, and discuss it. But written, printed, read, and discussed it very much was.

On the other side of the opinion line were those who thought he was no different than most anybody else who came to Alaska for the first time, braced for the challenges it offered, but without a full grasp and complete understanding of the place. They would argue in his defense that, besides, he did last a whole four months or more out/in there, and he did it alone! Thus, the question was rhetorically posed, asking who among the native and one-time cheechacko critics, alike, could have stuck it out solo as long as McCandless did, anyway? He had guts and conviction, maybe more than sense. But, maybe all he needed was just a little more luck, be it the Las Vegas or Nenana or some other kind. And if he had, and walked out, would his antics and trail and tributaries have otherwise been so well remembered?

Irrespective of which side of the snow line they may have stood, there was no denying the compelling nature of this debate both inside and outside the state. This is evidenced by the fact that, since the publishing of Into the Wild, and likely because of it, there has been a Midwestern band which has taken on the name Fairbanks 142, after the bus that would be the last home and first last resting place if this adventurer. And, at least one song has been written and recorded honoring his trip and his spirit: The Ballad of Chris McCandless (Ellis Paul, 2002, Speed of Trees).

It’s a strange situation,

A wild occupation

Livin' my life like a song

–The Wino and I Know, Jimmy Buffet, Living and Dying In 3/4 Time, © 1974

So, depending on who you might ask and where you might ask it, McCandless either was a foolish fuck-head or is a fledgling folk hero. As with many controversial figures, the truth about him, the reality of his exploits, and the meaning of the last two years and the final few days and hours of his life likely has him fall somewhere between being a fool and hearty.

I drive west down Stampede Trail where, over the eight miles to the appropriately dubbed Eightmile Lake, the road turns from graded gravel to packed dirt to moist tracks to ponding ruts to mostly muck and approaching muskeg, at which point it became completely impassable for the passenger car I was pushing down it. Getting out with tall grasses and subarctic scrub doing their best to envelop and reclaim the road, I gaze out farther to the west in what I figure to be the general direction of where that derelict Bus #142 still rests and rusts. I think of Chris McCandless for a long moment. What crosses my mind are some of the chancy things I have done in all of my, to this point, 42 years. And with respect to the act of universal hitchhiking, isn't 42 the answer, anyway?

It leads me to wonder for both he and me: What if? What if I had rolled snake eyes somewhere along the way? And, what if he had not? How would my life have been summed up if I had? And, how might his be developing if he was still alive? I then snap a couple of pictures, take a deep breath of fireweed perfume, and go on my way satisfied at having faced the place he faced.

Denali Donna

After negotiating the Stampede Trail road back to the Parks Highway and turning south, I do not stop until I reach the parking lot of the Denali National Park visitor’s center. Although content with first having found and gone down Stampede Trail and then reaching the famous park, still I am frustrated at having gone half way from Fairbanks to Anchorage and again coming up empty trolling for hitcher graffiti in Alaska. I become equally disappointed at the fact that a low cloud ceiling is sealing off my view of the 20,000-foot-high majesty that is Mt. McKinley. And, on top of that, I find out at the visitor center information desk that the seats on the free shuttle buses into the park proper are booked up for hours and I am just too cheap to fork out the ten bucks to buy the privilege of being able to take the car the fourteen-mile drive inside the park to not be able to see the mountain any better, anyways. So, I decide to leave; but, not before I get a compliment on the fading Dickies bib overalls I am wearing from a cute little blonde ranger manning the information desk donning the nameplate "Donna Middleson." I can’t help but think at that moment, as I thank her both for the information and for the wardrobe critique and walk away, of Maureen who, not being the greatest fan of these overalls, likely would have commented, with just a hint of jealousy, “Well, what do you expect! Alaska! What would they know about fashion up there, anyway?!”

Oh, Donna!

After negotiating the Stampede Trail road back to the Parks Highway and turning south, I do not stop until I reach the parking lot of the Denali National Park visitor’s center. Although content with first having found and gone down Stampede Trail and then reaching the famous park, still I am frustrated at having gone half way from Fairbanks to Anchorage and again coming up empty trolling for hitcher graffiti in Alaska. I become equally disappointed at the fact that a low cloud ceiling is sealing off my view of the 20,000-foot-high majesty that is Mt. McKinley. And, on top of that, I find out at the visitor center information desk that the seats on the free shuttle buses into the park proper are booked up for hours and I am just too cheap to fork out the ten bucks to buy the privilege of being able to take the car the fourteen-mile drive inside the park to not be able to see the mountain any better, anyways. So, I decide to leave; but, not before I get a compliment on the fading Dickies bib overalls I am wearing from a cute little blonde ranger manning the information desk donning the nameplate "Donna Middleson." I can’t help but think at that moment, as I thank her both for the information and for the wardrobe critique and walk away, of Maureen who, not being the greatest fan of these overalls, likely would have commented, with just a hint of jealousy, “Well, what do you expect! Alaska! What would they know about fashion up there, anyway?!”

Oh, Donna!

You Can Call Me Al

So, ego inflated--I barely am able to fit my head back into the car–I drive back out the front gates of the park and, since now having extra time which had been allotted to cursorily explore the park, I continue toward the small town of Cantwell some twenty-seven miles down The Parks. Just reaching highway cruising speed, to my right I see standing on the shoulder a hitchhiker laden with a few bags. Making the snap judgment decision, I think, “What the hell?” After pulling up to him and he pushing his stuff into the back seat and pulling himself in the front, we greet, he thanks me for stopping, and off we go.

An Asian American from Reno, his name was Al. For a living, he drives a big rig. For the rest of the time--three to six months at a time--he travels. Must be nice! We have a decent-enough discussion during the twenty minutes we sit beside each other as we view through the windshield the spectacular scenes unfolding on either side of the road that winds along the Nenana River as it drains its way north first to the Tanana and then the Yukon River, and then into the Bering Sea. As for Al, he's headed to Anchorage; me, not really any farther than Cantwell.

So, ego inflated--I barely am able to fit my head back into the car–I drive back out the front gates of the park and, since now having extra time which had been allotted to cursorily explore the park, I continue toward the small town of Cantwell some twenty-seven miles down The Parks. Just reaching highway cruising speed, to my right I see standing on the shoulder a hitchhiker laden with a few bags. Making the snap judgment decision, I think, “What the hell?” After pulling up to him and he pushing his stuff into the back seat and pulling himself in the front, we greet, he thanks me for stopping, and off we go.

An Asian American from Reno, his name was Al. For a living, he drives a big rig. For the rest of the time--three to six months at a time--he travels. Must be nice! We have a decent-enough discussion during the twenty minutes we sit beside each other as we view through the windshield the spectacular scenes unfolding on either side of the road that winds along the Nenana River as it drains its way north first to the Tanana and then the Yukon River, and then into the Bering Sea. As for Al, he's headed to Anchorage; me, not really any farther than Cantwell.

I let him off at a gas station at the far end of town, hopefully giving him the best chance of getting his next ride. He says he gives hitchhikers rides at times in his rig, even it's against trucking company policy. I say I guess I'm now doing the same in the company rental. After retrieving his things from the back seat, we shake hands and exchange first names. He then shuts the door and we part. Somewhat invigorated by this brief interaction, I buzz from light pole to road sign to light pole at either end of Cantwell in search of graffiti. Again, at first, with no luck. But then finally, on one of the poles, a faint message with words I can just not make out no matter how hard I squint or turned my head to gain another perspective on it. “Damn, almost!” I grunt under my breath at coming that close to getting my first thumber graffito in Alaska. Then, finally, on the back of the destination road sign which reads,

McKinley Park 27

Nenana 94

Fairbanks 149

there appears one lone graffito. It is brief. It is to the point. Simply, it states:

Tommy Salomi 4/79

I do not know who Tommy is or might have been, or what he was doing there nearly twenty years before. All I do know is that I have finally got one in Alaska, and it is his.

So, maybe Al from Reno has brought me a little good Nevada luck along the Nenana. Maybe it is the hitchhiker gods smiling down on me. Maybe it is just coincidence. Whatever it is, it also gets me to thinking that maybe weather isn’t necessarily a major factor in why I haven’t found any messages until now and that there must be more out there. In Alaska. Somewhere. Energized by this realization, along with my stop on Stampede Trail, with a flirtatious moment over overalls, and with giving a ride to Al–face-to-face and face-to-place--I work my way back north, first stopping back at the park visitor center to use the bathroom. Leaving the park for the second time in short order, heading north back to Fairbanks, this time I decide to check the guardrails I had failed to notice earlier–guess at the time I had my mind on my Dickies--where the main park access road merges with the Parks Highway. To my pleasant surprise, I find more than a dozen inscriptions that I had unknowingly passed by just before picking up Al. And, then, going back through Nenana, there are a couple more on a light pole I hadn’t check earlier in the day not far from the bridge over the Nenana River, a subarctic view which, according to the book, sparked Chris McCandless to recount to his ride, Jim Gallien, of his subtropic near-drowning experience in the Sea of Cortez.

Fast-forwarding now two weeks, to the end of my five-week work shift in Alaska. Before returning “outside” to rejoin my family, I rent a car and drive down to visit for a day Karen and Dave, old friends and one-time Lockheed coworkers who I knew from Las Vegas and who had moved and have lived in Anchorage for the past decade. On the way into Anchorage I find not one hitchhiker message anywhere around the city or on the roads leading into or exiting from it. Nothing south of Cantwell, where I had let Al off. Again, I am surprised at this and a bit disappointed. But, oh well, I am still in Alaska.

Driving the six hours each way between Fairbanks and Anchorage, I pass Denali National Park and Mt. McKinley. Again. Twice. One time, in the light of day heading down; the next, under a full moon on my return to Fairbanks. Equally frustrating is that each time the great mountain has been cloaked in low clouds that shields it from my view. Again. Twice. That very next morning, back in Fairbanks, in the gray of the long late-summer Alaskan dawn, I board the flight that will take me home to Las Vegas. It is August 9th and, as prearranged before I had agreed to take this remote work detail, I will make it back to celebrate the August 10th birthday of my daughter. The Alaska Airlines jet climbs to altitude south out from Fairbanks. We pass within eyeshot of Denali. Miraculously, or just by meteorological chance, the clouds part long enough for me to see the same full moon as it is setting in the steely-lavender sky behind Mt. McKinley. I finally get a chance to see the mountain. In the air. At the very last Alaska moment possible.

I smile. But, somewhere down below sits Fairbanks City Bus #142. The place Chris McCandless spent his own very last impossible earthly moments in Alaska. But, I am not think of him--six years almost to the day from when almost simultaneously he passed away and I began seeking out hitchhiker messages. I am just enjoying my own moment for what it is, reflecting on all that I have just done this past month and experiencing the anxious anticipation of seeing my family later today after all this time apart.

But, the nagging question remains: Whatever would have become of Chris McCandless if he had mustered the strength to walk, to hobble, to crawl, to scratch, to claw, to brush-break his way back out from the wild, to exit the Interior, to reach Stampede Trail to flag his next ride down the Parks Highway, and maybe even hitchhike back “outside” and on into dynamic anonymity? Who's to say? But, there is no doubt that he has become one cheechako who, like it or not and whether he ever really imagined it, has left his mark on Alaska. He also did leave graffiti up there. But, so far as I know, not on any light poles while hitchhiking. At least not any I could find. His were written on the walls of Fairbanks City Bus #142. One of these was his take on the song King of the Road by Roger Miller, who as it turned out, also passed on in 1992. This graffito states:

McKinley Park 27

Nenana 94

Fairbanks 149

there appears one lone graffito. It is brief. It is to the point. Simply, it states:

Tommy Salomi 4/79

I do not know who Tommy is or might have been, or what he was doing there nearly twenty years before. All I do know is that I have finally got one in Alaska, and it is his.

So, maybe Al from Reno has brought me a little good Nevada luck along the Nenana. Maybe it is the hitchhiker gods smiling down on me. Maybe it is just coincidence. Whatever it is, it also gets me to thinking that maybe weather isn’t necessarily a major factor in why I haven’t found any messages until now and that there must be more out there. In Alaska. Somewhere. Energized by this realization, along with my stop on Stampede Trail, with a flirtatious moment over overalls, and with giving a ride to Al–face-to-face and face-to-place--I work my way back north, first stopping back at the park visitor center to use the bathroom. Leaving the park for the second time in short order, heading north back to Fairbanks, this time I decide to check the guardrails I had failed to notice earlier–guess at the time I had my mind on my Dickies--where the main park access road merges with the Parks Highway. To my pleasant surprise, I find more than a dozen inscriptions that I had unknowingly passed by just before picking up Al. And, then, going back through Nenana, there are a couple more on a light pole I hadn’t check earlier in the day not far from the bridge over the Nenana River, a subarctic view which, according to the book, sparked Chris McCandless to recount to his ride, Jim Gallien, of his subtropic near-drowning experience in the Sea of Cortez.

Fast-forwarding now two weeks, to the end of my five-week work shift in Alaska. Before returning “outside” to rejoin my family, I rent a car and drive down to visit for a day Karen and Dave, old friends and one-time Lockheed coworkers who I knew from Las Vegas and who had moved and have lived in Anchorage for the past decade. On the way into Anchorage I find not one hitchhiker message anywhere around the city or on the roads leading into or exiting from it. Nothing south of Cantwell, where I had let Al off. Again, I am surprised at this and a bit disappointed. But, oh well, I am still in Alaska.

Driving the six hours each way between Fairbanks and Anchorage, I pass Denali National Park and Mt. McKinley. Again. Twice. One time, in the light of day heading down; the next, under a full moon on my return to Fairbanks. Equally frustrating is that each time the great mountain has been cloaked in low clouds that shields it from my view. Again. Twice. That very next morning, back in Fairbanks, in the gray of the long late-summer Alaskan dawn, I board the flight that will take me home to Las Vegas. It is August 9th and, as prearranged before I had agreed to take this remote work detail, I will make it back to celebrate the August 10th birthday of my daughter. The Alaska Airlines jet climbs to altitude south out from Fairbanks. We pass within eyeshot of Denali. Miraculously, or just by meteorological chance, the clouds part long enough for me to see the same full moon as it is setting in the steely-lavender sky behind Mt. McKinley. I finally get a chance to see the mountain. In the air. At the very last Alaska moment possible.

I smile. But, somewhere down below sits Fairbanks City Bus #142. The place Chris McCandless spent his own very last impossible earthly moments in Alaska. But, I am not think of him--six years almost to the day from when almost simultaneously he passed away and I began seeking out hitchhiker messages. I am just enjoying my own moment for what it is, reflecting on all that I have just done this past month and experiencing the anxious anticipation of seeing my family later today after all this time apart.

But, the nagging question remains: Whatever would have become of Chris McCandless if he had mustered the strength to walk, to hobble, to crawl, to scratch, to claw, to brush-break his way back out from the wild, to exit the Interior, to reach Stampede Trail to flag his next ride down the Parks Highway, and maybe even hitchhike back “outside” and on into dynamic anonymity? Who's to say? But, there is no doubt that he has become one cheechako who, like it or not and whether he ever really imagined it, has left his mark on Alaska. He also did leave graffiti up there. But, so far as I know, not on any light poles while hitchhiking. At least not any I could find. His were written on the walls of Fairbanks City Bus #142. One of these was his take on the song King of the Road by Roger Miller, who as it turned out, also passed on in 1992. This graffito states:

"Two years he walks the earth. No phone, no pool, no pets, no cigarettes. Ultimate freedom. An extremist. An aesthetic voyager whose home is the road. Escaped from Atlanta. Thou shalt not return, 'cause “the West is the Best.” And now after two rambling years comes the final and greatest adventure. The climactic battle to kill the false being within and victoriously conclude the spiritual pilgrimage. Ten days and nights of freight trains and hitchhiking bring him to the great white north. No longer to be poisoned by civilization he flees, and walks alone upon the land to become lost in the wild. Alexander Supertramp, May 1992."

As for me, am I just a Mark who left Alaska with no mark? Unlike McCandless, I manage to make my way back home. And it is back to the subdivision, to three community pools, to several pets, to my one love, and to our three desert rug rats. And to FEP and a regular job with benefits, and to innumerable commitments.

Things are okay with me these days

Got a good job, got a good office

Got a new wife, got a new life

And the family's fine

--Scenes From An Italian Restaurant, Stranger, Billy Joel, 1977

But, ironically, while I was free to go anywhere and glad to choose to go home to my responsibilities, Chris McCandless died a prisoner of the wild in Fairbanks Bus # 142. Go figure. Which brings to mind the following from someone called Ishmael:

Things are okay with me these days

Got a good job, got a good office

Got a new wife, got a new life

And the family's fine

--Scenes From An Italian Restaurant, Stranger, Billy Joel, 1977

But, ironically, while I was free to go anywhere and glad to choose to go home to my responsibilities, Chris McCandless died a prisoner of the wild in Fairbanks Bus # 142. Go figure. Which brings to mind the following from someone called Ishmael:

"...Though I cannot tell why it was exactly that those stage managers, the Fates, put me down for this shabby part...when others were set down for magnificent parts in high tragedies, and short and easy parts in genteel comedies, and jolly parts in farces--though I cannot tell why this was exactly; yet, now that I recall all the circumstances, I think I can see a little into the springs and motives which being cunningly presented to me under various disguises, induced me to set about performing the part I did, besides cajoling me into the delusion that it was a choice resulting from my own unbiased freewill and discriminating judgment."

–Voice of Ishmael speculating why he signed on to an ill-fated whaler; Chapter 1, Moby Dick, Herman Melville, 1851.

And, when I do go home, the street on which my house is located--the place held the focal points of all these responsibilities–happens to be called Livengood Drive. Livengood is but one short block long nestled in a typical Las Vegas stucco-and-tile residential subdivision. The street was named for a guy of some position of authority in the county’s Department of Public Works. I happened to run into this Mr. Urban Livengood just by chance six years after returning from Alaska while helping a mutual Las Vegas friend move. Hearing that I lived on the street bearing his name, and my mentioning to him that I had been to the town of Livengood in Alaska just northwest of Fairbanks because of my having lived on the street of the same name, he went on to claim to be a blood relation to Jay Livengood, an adventurer from Ohio and a successful Alaska gold prospector of the early 1900s for whom this small, one-sled-dog town of Livengood, Alaska, was named. Aside from living on the street, I sense I have not much else in common--neither feeling superior to or sub-Urban--with the man. And about the only thing else this Alaskan hamlet and the Las Vegas street shared aside from the familial name is having about the same total number of homes and people living in or on each.

Finally, soon after meeting this Livengood relative, while finally getting around to editing this essay I first drafted in Fairbanks, not only would I find my way to do some work down at Callville Bay where Chris McCandless passed through and first hitched from, I would also move my family from our Livengood Drive house of twelve years to another place a short distance away on yet another one-short-block-long street, called Sandy Creek. There happens to also be a short watercourse called Sandy Creek near Healy, Alaska, where Stampede Trail turns off The Parks, named not for a fine-grained substrate as one might guess, but rather as it is claimed, for a woman named Sandra, the daughter of the one-time owner of an area lignite coal mine. Now, Sandy Creek Drive in Las Vegas has only one road intersecting it, which is called Voyager Street--presumably not anybody’s family name. Whether this Voyager is aesthetic is in the senses of the beholder and what would one by the name of Alexander Supertramp say about it? All I do know about it is that when I head out from my family home around the corner from it that we have settled into, to venture outside and into the rest of the world, and then when I return from wherever it was I might have ventured to, I travel down Voyager to do it!

So, when the day comes to settle down,

Who's to blame if you're not around?

You took the long way home

You took the long way home...........

-- Take the Long Way Home, Breakfast in America, Supertramp, 1979

Finally, soon after meeting this Livengood relative, while finally getting around to editing this essay I first drafted in Fairbanks, not only would I find my way to do some work down at Callville Bay where Chris McCandless passed through and first hitched from, I would also move my family from our Livengood Drive house of twelve years to another place a short distance away on yet another one-short-block-long street, called Sandy Creek. There happens to also be a short watercourse called Sandy Creek near Healy, Alaska, where Stampede Trail turns off The Parks, named not for a fine-grained substrate as one might guess, but rather as it is claimed, for a woman named Sandra, the daughter of the one-time owner of an area lignite coal mine. Now, Sandy Creek Drive in Las Vegas has only one road intersecting it, which is called Voyager Street--presumably not anybody’s family name. Whether this Voyager is aesthetic is in the senses of the beholder and what would one by the name of Alexander Supertramp say about it? All I do know about it is that when I head out from my family home around the corner from it that we have settled into, to venture outside and into the rest of the world, and then when I return from wherever it was I might have ventured to, I travel down Voyager to do it!

So, when the day comes to settle down,

Who's to blame if you're not around?

You took the long way home

You took the long way home...........

-- Take the Long Way Home, Breakfast in America, Supertramp, 1979

With all this, the following are the hitchhiker inscriptions taken from the guardrail at the entrance to Denali National Park on Alaska Route 3/George Parks Highway South, on July 26, 1998:

Bob here again

Real fine day from Fairbanks

Solstice was excellent

I here puffin a gnarly one

Thinkin ah perc___[?] way up north - dontcha know

Feels like a miracle => Bertha => Good lovin' `82

Rick loves Annie

Ron D. Brower Pt. Barrow Top of the world 6-11-95

Mike Boglioli was here 6/19/86

Mike Neese Greg Hill Heide Spencer First we smoke 6/5/81

Eric Holland was here `93 God Bless Hitch Hikers

Kes + George from North Carolina Can't get a fuckin ride

David A. Metcalf loves Arlene Tunutmoak

Eight years in Denali

It ain't heaven / it's freakin hell

Corruption on all levels

America is the victim

Troy Putnam and Jeff were here

Couldn't get a fuckin ride Its raining

Harry Sept 20 97 Shurbische Alb

Post Grad/Stanford

78 CIA 11/78 - 2/79

My life will be best between here and Canada

Find bud in foam cup

Gift of love from Howard

3/28/95 => [arrow pointing to open-ended guardrail support]

I killed a 6-pack just to watch it die

Next town south is Cantwell / Good luck from there

High times in Alaska! Smoke more pot & tax hemp

I voted and it didn't help TAZ 98

And, on Parks Highway-South, in Nenana, Alaska, on a light pole on side of road with no on-ramps:

Dan & David from New Orleans 5/90 Good Luck

NOMAD 5/5/87?89?

Bob here again

Real fine day from Fairbanks

Solstice was excellent

I here puffin a gnarly one

Thinkin ah perc___[?] way up north - dontcha know

Feels like a miracle => Bertha => Good lovin' `82

Rick loves Annie

Ron D. Brower Pt. Barrow Top of the world 6-11-95

Mike Boglioli was here 6/19/86

Mike Neese Greg Hill Heide Spencer First we smoke 6/5/81

Eric Holland was here `93 God Bless Hitch Hikers

Kes + George from North Carolina Can't get a fuckin ride

David A. Metcalf loves Arlene Tunutmoak

Eight years in Denali

It ain't heaven / it's freakin hell

Corruption on all levels

America is the victim

Troy Putnam and Jeff were here

Couldn't get a fuckin ride Its raining

Harry Sept 20 97 Shurbische Alb

Post Grad/Stanford

78 CIA 11/78 - 2/79

My life will be best between here and Canada

Find bud in foam cup

Gift of love from Howard

3/28/95 => [arrow pointing to open-ended guardrail support]

I killed a 6-pack just to watch it die

Next town south is Cantwell / Good luck from there

High times in Alaska! Smoke more pot & tax hemp

I voted and it didn't help TAZ 98

And, on Parks Highway-South, in Nenana, Alaska, on a light pole on side of road with no on-ramps:

Dan & David from New Orleans 5/90 Good Luck

NOMAD 5/5/87?89?