Run-up to the Hitch

As much as any story has an exact beginning, here is where the hitchhiking part of my story starts.

Desert Desserts

I concluded from conferring with my AAA map, consulting with the bus station ticket counter clerk in Albuquerque, and deliberating with the Greyhound driver upon boarding his bus bound for LA, that in order to get to Alpine, Arizona, I would have to be dropped off on Interstate 40 at its western junction with US Route 666 in the town of Sanders, Arizona.

I did not intend to take lightly the task of contending with making it through the 100-plus miles under mid-August, southwestern midday sun. The desert was a mysterious land of myth and rural legend to a New York City city boy; a dry and forbidding place. It was sparingly mentioned in the Boy Scout Handbook along with the prickly pear cactus, which it classified as an edible plant–flora as alien to me at the time as I was in the land in which it flourished. But, if nothing else, my years of scout training made me realistic enough to take a stab at being prepared for the plausibility of being stranded many miles from anywhere and anyone. And my many more years of watching westerns on TV had planted visions of snake-necked, sharp-beaked buzzards circling above and buzzard-necked, sharp-fanged rattlers coiled below as a lone traveler hiked and then stumbled and then tripped and then fell and then crawled on all-fours past sage brush and over sand dunes and by sun-bleached longhorn skulls, finally gasping for breath and rasping for “...water...water.....water........” before collapsing prostrate in the dust. Such images caused me to stop at a grocery store in Albuquerque on the way to the Greyhound station for packs of salted nuts, sticks of beef jerky, bars of chocolate, and a couple of navel oranges. I cannot say whether these provisions, which I had stuffed into the pouches of my pack along with a canteen filled with water from the bus station water fountain--there was no bottled water back then--would have sufficed in a pinch if I had gotten stranded somewhere out on panorama of Arizona. But I felt at the time that this cache would hold me through the worst of whatever may challenge me "out there"--at least through the first couple of nights and days. After all, I could always eat parts of the prickly pear.

Orange you Glad I Didn't Say Prickly Pear

Somewhere between Albuquerque and the Arizona state line, at the transient intersection of he and me, I struck up a conversation with a fellow traveler sitting next to me who was from Paris, France. By the name of Jean-Claude Ruben, he and I, along with the German girl I had just left behind, were all about the same age and were sharing a united state of an American adventure. As we bantered on about my country and his, and this new land we were each experiencing at the same time for the first time, the bus left New Mexico and slowed to a required stop at what’s called an agricultural inspection station or the police vege-station. After pulling into a parking stall reserved for big rigs and buses, on boarded an officious uniform-clad official from the AZ Ag Department. Slowly and deliberately he plodded down the aisle, stony-faced and in the fashion of, but without the grace, of an airline stewardess (they still called them stewardesses back then) asking if you wanted the beef, chicken, or vegetarian meal. In this case, the subject was of the vegetable variety, only, and conversely, it had to do with a food order being given by the person in uniform, not taken. His mission was to make certain that certain fruits and vegetables did not enter Arizona, as part of a front line of biological defense against the inadvertent importation (also know as hitchhiking) into Arizona of potential vectors or otherwise infected or diseased produce of the kinds also commercially grown within the state limits. I wasn’t quite sure what agronomic problems, if any, my two coveted Albuquerque-acquired oranges might cause in the middle of a region that, from my vantage point and myopic view, seemed to have trouble growing much of any form of plant life at all, no less those categorized as a citricultural cash crop. But far be it from me to, at that moment, debate this issue with a member of the fruit fuzz who was buzzing down my way. So, albeit a small one, I was left with a moral dilemma--stuck between a throw pillow and a soft place, or an angel and the deep-blue sky, so to speak. Curiously as I saw it, the question I found myself facing had two answers that were diametrically opposed to each other with respect to my boy scout training; responses that caused me to find myself with one foot on the boat to survival and the other on the dock of ethics. Do I come clean and fess up that, yes, I am in possession of some vegetable matter that anywhere else in my experience was legally and socially encouraged to be obtained and consumed? Or do I just say, “No,” and carry my concealed contraband across this seemingly arbitrary agrigeopolitical borderline? Was I to be honest and rat out the little, round, navel beauties, or to be loyal to my sense of subsistence and do my best to be prepared? I looked at those blemish-free orange orbs as small stores of precious, sweet-golden liquid and as watery round reservoirs that very well may soon play a role in keeping my body from a state of dehydration in the State of Arizona. So, the decision was easy. I told the crop cop a little Creamsicle lie. This act of “citral” disobedience did not cause the demise of Arizona’s agricultural industry. Nor did I die of thirst out on its back roads. So, as they say in these aridlands regarding to water resource concerns, it was a wash.

After the brief interlude of inspection and introspection was complete--the bus may have been lightened by a few peaches or nectarines confiscated out of someone’s lunch by the vegetative state police--the bus pulled back onto I-40–anxious anticipation began welling up in me as I knew I was getting close to my stop. Using the seatbacks for balance in the manner in which a skier uses poles, I slalomed my way up to the front to remind to the driver that I wanted off at Sanders. Dutifully and without taking his eyes off the road, he nodded in concurrence and I made it back to my seat to wait for his signal for me to bring my stuff forward. Perched forward on the edge o my seat, one foot planted in the aisle, I kept one eye on my possessions in the overhead luggage bin and the other on the back of the bus driver’s head.

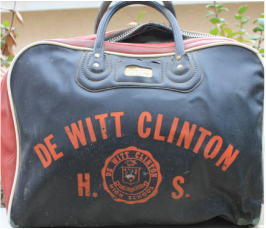

As my brief tête-à-tête with Jean-Claude was about to terminate, we wished each other a mutual bon voyage. As we did, I sensed the massive coach begin to slow and got the hand-signal from the coachman to get myself ready, which I acknowledged via eye contact and a nod using his interior rear view mirror. As the vehicle gently veered across the solid white line I swung into action. Upon shaking the Frenchman’s hand, I took the breath of a detainee being released from confinement, reached for my backpack, and clumsily (there’s just no graceful way to accomplish this) eased it out from its constraints in the open-air overhead compartment so as to not smack any of the my fellow riders up the side or down atop their heads either with its bulk or a stray strap dangling from it. After slipping it snugly onto my shoulders, I reached with my left hand beneath my now-vacant seat to grab the only other piece of luggage I was toting with me: my old, worn black-and-red DeWitt Clinton High School book bag. With my right hand, I steadied myself and headed forward as the bus swayed and the brakes grabbed hold. In the process, I began to feel many pairs of eyes from the three-fourths-full bus train themselves on the spectacle that was me—at least those that bothered to look up from the nod or the book or whatever distraction they were using to snuff out the time they desperately were trying to kill.

Now, not that this never happens, but a passenger voluntarily getting let off on the break-down lane of an interstate is not a regular occurrence. This was not a “stop” in the classical Greyhound depot and post-house sense. Being longer in hair than in the tooth, I couldn’t quite decipher the meanings of the expressions on faces of some of the riders as I lumbered to the front. Although I was cognizant enough to note that I was acting as the receiver for this broadcast of telepathic waves of thought and emotion, it took me some time later, when my hair was shorter and teeth were longer, to understand that, although all those looks were directed my way, they did not necessarily contain universal sentiments. The one thing common among their stares was a curiosity as to why on Earth I was getting off where on Earth the bus was stopping to allow me to do so; similar to what has been said about sky diving and why would someone throw himself out of a perfectly good plane? Thus, I’m sure some passengers were bewildered as to why anyone would let themselves be dumped on the side of the road in such a seemingly God-forsaken (-mistaken?) place. Others may have marveled at the fact that I would have the nerve to let myself be abandoned on an empty stretch of highway and that I was either brave or foolish to foist this predicament upon myself. A few may have just figured I lived close by or was rendezvousing with someone who did. I’m sure, still others could have cared less about my story and would just as soon that the backpacking speed bump I had become on the road of their trip be dispatched with minimal delay so that they could continue on with their own story and be snipped free of their entanglement in the thread of mine.

Beside the Road, Beside Myself

As I crossed the shoe-scuffed, stand-behind white line on the slip-resistant floor and reached even with the seated driver, the bus eased to a full stop. As it did, he turned to me and, with what seemed like genuine fatherly concern, kindly offered one last time, “You sure you want to get off here?” The tone in his voice had a hint of his coming to the realization that, although once I had left his bus he was no longer professionally responsible for my safety, he had a moral obligation to at least attempt to save me from myself. I would have nothing to do with such thoughts except to appreciate his implied, nested overture of advice--not at all unlike my own father's admonition a few weeks before ironically about taking the bus. But, there was nothing I was more sure of at that moment than the fact that I was going to climb down those three oversized, white-margined steps as soon as the folding door they descended to opened to the asphalt below and to the great-wide-open to set me free.

It was not that I consciously thought that all things were possible or that I was invincible. It was much more that I never thought to consider the risks and the impossibilities--notwithstanding the being-stranded scenario. It also never occurred to me that I wouldn’t be alright, or that any great harm may come to me, or that I wouldn’t eventually get to where I wanted to go and get there intact and whole. I never gave a second thought to the probability that there would be a little hardship. This was a given and a welcome challenge. If I was not prepared for that or if it worried me in any measure, I simply would have stayed on the bus or, actually, just remained home in The Bronx—each of which carried its own degree of discomfort, difficulty, and danger, anyway. And both of which happened to afford me some of the life experiences that helped to prepare me for the leg of the journey on which I was about to embark. But, the worry was for the adults, the rest was for me.

So, like a skydiver awaiting the pilot’s command to jump, I listened for the bus driver’s permission to take the step that would begin my horizontal free-fall down a perpendicular highway and into the wild black-top yonder. And while I didn’t yell “Geronimo!,” doing so may have been an appropriate response due to my proximity to and soon-to-be direction south toward some of that great Apache medicine man’s old stomping and was-stomped-on grounds. Ironically, Geronimo’s birth name was Goyathlay, which means one who yawns in Chiricahuan. Typically, when people yell his given-taken name, it’s not a yawning matter. Besides, I always thought that “Geronimo” must be Apache for “Don’t try this at home!”

Oh, and if I don't have a car, I'll hitch

I got a thumb and she's a son of a bitch...”

--Worst Comes to Worst, Piano Man, Billy Joel, 1973

Then the bus stopped, the retractable door collapsed open, and I pushed myself past the two shiny, upright stainless steel posts I had been gripping with adrenaline-induced sweaty hands. As I did, the bus driver earnestly exclaimed, “So long, young man. Best of luck to ya’,” as I slipped past him with my briny mitts sliding down the smooth, cool handrail and my legs stretching down those super-sized steps. With the sun and open air hitting me in the face as my hiking boots reached the road surface, I took a step or two forward while bending my back and knees to counter the forces of inertia which would just as soon carry me off into the desert and flat on my face, I steadied myself, straightened up, about-faced, and, thanking the man for his good wishes, waved and said good bye. As he nodded back in acknowledgment, I heard those distinctive sounds only buses make--the squeaky, gaseous, harmonious skwooosh of the door and air brakes and grind of the transmission performing their respective, independent functions followed by the dieselly vrrrroooom of the engine laboring to bring the vehicle’s mass into motion. The ferry of the terra firma adorned with its elegantly elongated canine icon logo then eased past me as I strained to see the faint images of its passengers looking down at me through the tinted glass. As the Greyhound began to gather speed to resume its standard route and make its schedule, a thin blue-grey veil of spent-fuel fumes spewed from its high-tail pipe was sucked back down into the draft it created, which then wrapped around me as I stood watching and listening mute and motionless. The bus disappeared from my view about as quickly as the exhaust it left behind dissipated in to the rich, perspectiveless blue of the cloud-free desert sky.

It wasn’t until a disquieting silence had engulfed me just as the nauseatingly sweet smoke had done seconds before that I had a clue as to the fix I had broken myself into. Ironically, although I made plans to deal with the desert heat, I had not anticipated freezing up, which I did for one momentous, momentumless moment. And then, in another instant I felt I knew what Hitchcock’s character, Roger Thornhill, might have been thinking right after the bus left him on the shoulder of the dusty, feature-starved Midwestern cornfield landscape along Highway 41. Unlike Thornhill, however, I was angling somewhere to the southwest by south. And, since this also was in the general direction of ancestral Apache lands, perhaps a more appropriate response to my situation may have been my request for guidance--so that it might be lightly carried to his spirit like a gossamer on the warm desert breeze--by ever-so softly whispering, “Yo, G-e-r-o-n-i-m-o?”

© 2013 Mark E. Silverstein

Desert Desserts

I concluded from conferring with my AAA map, consulting with the bus station ticket counter clerk in Albuquerque, and deliberating with the Greyhound driver upon boarding his bus bound for LA, that in order to get to Alpine, Arizona, I would have to be dropped off on Interstate 40 at its western junction with US Route 666 in the town of Sanders, Arizona.

I did not intend to take lightly the task of contending with making it through the 100-plus miles under mid-August, southwestern midday sun. The desert was a mysterious land of myth and rural legend to a New York City city boy; a dry and forbidding place. It was sparingly mentioned in the Boy Scout Handbook along with the prickly pear cactus, which it classified as an edible plant–flora as alien to me at the time as I was in the land in which it flourished. But, if nothing else, my years of scout training made me realistic enough to take a stab at being prepared for the plausibility of being stranded many miles from anywhere and anyone. And my many more years of watching westerns on TV had planted visions of snake-necked, sharp-beaked buzzards circling above and buzzard-necked, sharp-fanged rattlers coiled below as a lone traveler hiked and then stumbled and then tripped and then fell and then crawled on all-fours past sage brush and over sand dunes and by sun-bleached longhorn skulls, finally gasping for breath and rasping for “...water...water.....water........” before collapsing prostrate in the dust. Such images caused me to stop at a grocery store in Albuquerque on the way to the Greyhound station for packs of salted nuts, sticks of beef jerky, bars of chocolate, and a couple of navel oranges. I cannot say whether these provisions, which I had stuffed into the pouches of my pack along with a canteen filled with water from the bus station water fountain--there was no bottled water back then--would have sufficed in a pinch if I had gotten stranded somewhere out on panorama of Arizona. But I felt at the time that this cache would hold me through the worst of whatever may challenge me "out there"--at least through the first couple of nights and days. After all, I could always eat parts of the prickly pear.

Orange you Glad I Didn't Say Prickly Pear

Somewhere between Albuquerque and the Arizona state line, at the transient intersection of he and me, I struck up a conversation with a fellow traveler sitting next to me who was from Paris, France. By the name of Jean-Claude Ruben, he and I, along with the German girl I had just left behind, were all about the same age and were sharing a united state of an American adventure. As we bantered on about my country and his, and this new land we were each experiencing at the same time for the first time, the bus left New Mexico and slowed to a required stop at what’s called an agricultural inspection station or the police vege-station. After pulling into a parking stall reserved for big rigs and buses, on boarded an officious uniform-clad official from the AZ Ag Department. Slowly and deliberately he plodded down the aisle, stony-faced and in the fashion of, but without the grace, of an airline stewardess (they still called them stewardesses back then) asking if you wanted the beef, chicken, or vegetarian meal. In this case, the subject was of the vegetable variety, only, and conversely, it had to do with a food order being given by the person in uniform, not taken. His mission was to make certain that certain fruits and vegetables did not enter Arizona, as part of a front line of biological defense against the inadvertent importation (also know as hitchhiking) into Arizona of potential vectors or otherwise infected or diseased produce of the kinds also commercially grown within the state limits. I wasn’t quite sure what agronomic problems, if any, my two coveted Albuquerque-acquired oranges might cause in the middle of a region that, from my vantage point and myopic view, seemed to have trouble growing much of any form of plant life at all, no less those categorized as a citricultural cash crop. But far be it from me to, at that moment, debate this issue with a member of the fruit fuzz who was buzzing down my way. So, albeit a small one, I was left with a moral dilemma--stuck between a throw pillow and a soft place, or an angel and the deep-blue sky, so to speak. Curiously as I saw it, the question I found myself facing had two answers that were diametrically opposed to each other with respect to my boy scout training; responses that caused me to find myself with one foot on the boat to survival and the other on the dock of ethics. Do I come clean and fess up that, yes, I am in possession of some vegetable matter that anywhere else in my experience was legally and socially encouraged to be obtained and consumed? Or do I just say, “No,” and carry my concealed contraband across this seemingly arbitrary agrigeopolitical borderline? Was I to be honest and rat out the little, round, navel beauties, or to be loyal to my sense of subsistence and do my best to be prepared? I looked at those blemish-free orange orbs as small stores of precious, sweet-golden liquid and as watery round reservoirs that very well may soon play a role in keeping my body from a state of dehydration in the State of Arizona. So, the decision was easy. I told the crop cop a little Creamsicle lie. This act of “citral” disobedience did not cause the demise of Arizona’s agricultural industry. Nor did I die of thirst out on its back roads. So, as they say in these aridlands regarding to water resource concerns, it was a wash.

After the brief interlude of inspection and introspection was complete--the bus may have been lightened by a few peaches or nectarines confiscated out of someone’s lunch by the vegetative state police--the bus pulled back onto I-40–anxious anticipation began welling up in me as I knew I was getting close to my stop. Using the seatbacks for balance in the manner in which a skier uses poles, I slalomed my way up to the front to remind to the driver that I wanted off at Sanders. Dutifully and without taking his eyes off the road, he nodded in concurrence and I made it back to my seat to wait for his signal for me to bring my stuff forward. Perched forward on the edge o my seat, one foot planted in the aisle, I kept one eye on my possessions in the overhead luggage bin and the other on the back of the bus driver’s head.

As my brief tête-à-tête with Jean-Claude was about to terminate, we wished each other a mutual bon voyage. As we did, I sensed the massive coach begin to slow and got the hand-signal from the coachman to get myself ready, which I acknowledged via eye contact and a nod using his interior rear view mirror. As the vehicle gently veered across the solid white line I swung into action. Upon shaking the Frenchman’s hand, I took the breath of a detainee being released from confinement, reached for my backpack, and clumsily (there’s just no graceful way to accomplish this) eased it out from its constraints in the open-air overhead compartment so as to not smack any of the my fellow riders up the side or down atop their heads either with its bulk or a stray strap dangling from it. After slipping it snugly onto my shoulders, I reached with my left hand beneath my now-vacant seat to grab the only other piece of luggage I was toting with me: my old, worn black-and-red DeWitt Clinton High School book bag. With my right hand, I steadied myself and headed forward as the bus swayed and the brakes grabbed hold. In the process, I began to feel many pairs of eyes from the three-fourths-full bus train themselves on the spectacle that was me—at least those that bothered to look up from the nod or the book or whatever distraction they were using to snuff out the time they desperately were trying to kill.

Now, not that this never happens, but a passenger voluntarily getting let off on the break-down lane of an interstate is not a regular occurrence. This was not a “stop” in the classical Greyhound depot and post-house sense. Being longer in hair than in the tooth, I couldn’t quite decipher the meanings of the expressions on faces of some of the riders as I lumbered to the front. Although I was cognizant enough to note that I was acting as the receiver for this broadcast of telepathic waves of thought and emotion, it took me some time later, when my hair was shorter and teeth were longer, to understand that, although all those looks were directed my way, they did not necessarily contain universal sentiments. The one thing common among their stares was a curiosity as to why on Earth I was getting off where on Earth the bus was stopping to allow me to do so; similar to what has been said about sky diving and why would someone throw himself out of a perfectly good plane? Thus, I’m sure some passengers were bewildered as to why anyone would let themselves be dumped on the side of the road in such a seemingly God-forsaken (-mistaken?) place. Others may have marveled at the fact that I would have the nerve to let myself be abandoned on an empty stretch of highway and that I was either brave or foolish to foist this predicament upon myself. A few may have just figured I lived close by or was rendezvousing with someone who did. I’m sure, still others could have cared less about my story and would just as soon that the backpacking speed bump I had become on the road of their trip be dispatched with minimal delay so that they could continue on with their own story and be snipped free of their entanglement in the thread of mine.

Beside the Road, Beside Myself

As I crossed the shoe-scuffed, stand-behind white line on the slip-resistant floor and reached even with the seated driver, the bus eased to a full stop. As it did, he turned to me and, with what seemed like genuine fatherly concern, kindly offered one last time, “You sure you want to get off here?” The tone in his voice had a hint of his coming to the realization that, although once I had left his bus he was no longer professionally responsible for my safety, he had a moral obligation to at least attempt to save me from myself. I would have nothing to do with such thoughts except to appreciate his implied, nested overture of advice--not at all unlike my own father's admonition a few weeks before ironically about taking the bus. But, there was nothing I was more sure of at that moment than the fact that I was going to climb down those three oversized, white-margined steps as soon as the folding door they descended to opened to the asphalt below and to the great-wide-open to set me free.

It was not that I consciously thought that all things were possible or that I was invincible. It was much more that I never thought to consider the risks and the impossibilities--notwithstanding the being-stranded scenario. It also never occurred to me that I wouldn’t be alright, or that any great harm may come to me, or that I wouldn’t eventually get to where I wanted to go and get there intact and whole. I never gave a second thought to the probability that there would be a little hardship. This was a given and a welcome challenge. If I was not prepared for that or if it worried me in any measure, I simply would have stayed on the bus or, actually, just remained home in The Bronx—each of which carried its own degree of discomfort, difficulty, and danger, anyway. And both of which happened to afford me some of the life experiences that helped to prepare me for the leg of the journey on which I was about to embark. But, the worry was for the adults, the rest was for me.

So, like a skydiver awaiting the pilot’s command to jump, I listened for the bus driver’s permission to take the step that would begin my horizontal free-fall down a perpendicular highway and into the wild black-top yonder. And while I didn’t yell “Geronimo!,” doing so may have been an appropriate response due to my proximity to and soon-to-be direction south toward some of that great Apache medicine man’s old stomping and was-stomped-on grounds. Ironically, Geronimo’s birth name was Goyathlay, which means one who yawns in Chiricahuan. Typically, when people yell his given-taken name, it’s not a yawning matter. Besides, I always thought that “Geronimo” must be Apache for “Don’t try this at home!”

Oh, and if I don't have a car, I'll hitch

I got a thumb and she's a son of a bitch...”

--Worst Comes to Worst, Piano Man, Billy Joel, 1973

Then the bus stopped, the retractable door collapsed open, and I pushed myself past the two shiny, upright stainless steel posts I had been gripping with adrenaline-induced sweaty hands. As I did, the bus driver earnestly exclaimed, “So long, young man. Best of luck to ya’,” as I slipped past him with my briny mitts sliding down the smooth, cool handrail and my legs stretching down those super-sized steps. With the sun and open air hitting me in the face as my hiking boots reached the road surface, I took a step or two forward while bending my back and knees to counter the forces of inertia which would just as soon carry me off into the desert and flat on my face, I steadied myself, straightened up, about-faced, and, thanking the man for his good wishes, waved and said good bye. As he nodded back in acknowledgment, I heard those distinctive sounds only buses make--the squeaky, gaseous, harmonious skwooosh of the door and air brakes and grind of the transmission performing their respective, independent functions followed by the dieselly vrrrroooom of the engine laboring to bring the vehicle’s mass into motion. The ferry of the terra firma adorned with its elegantly elongated canine icon logo then eased past me as I strained to see the faint images of its passengers looking down at me through the tinted glass. As the Greyhound began to gather speed to resume its standard route and make its schedule, a thin blue-grey veil of spent-fuel fumes spewed from its high-tail pipe was sucked back down into the draft it created, which then wrapped around me as I stood watching and listening mute and motionless. The bus disappeared from my view about as quickly as the exhaust it left behind dissipated in to the rich, perspectiveless blue of the cloud-free desert sky.

It wasn’t until a disquieting silence had engulfed me just as the nauseatingly sweet smoke had done seconds before that I had a clue as to the fix I had broken myself into. Ironically, although I made plans to deal with the desert heat, I had not anticipated freezing up, which I did for one momentous, momentumless moment. And then, in another instant I felt I knew what Hitchcock’s character, Roger Thornhill, might have been thinking right after the bus left him on the shoulder of the dusty, feature-starved Midwestern cornfield landscape along Highway 41. Unlike Thornhill, however, I was angling somewhere to the southwest by south. And, since this also was in the general direction of ancestral Apache lands, perhaps a more appropriate response to my situation may have been my request for guidance--so that it might be lightly carried to his spirit like a gossamer on the warm desert breeze--by ever-so softly whispering, “Yo, G-e-r-o-n-i-m-o?”

© 2013 Mark E. Silverstein