Let the Cowboys Ride

Howdy, Pardners

My exploration into the exotic world of common ranching and farming equipment was abruptly curtailed by the growing hum of approaching southbound traffic. The sound brought me back to the reality of what it was I was supposed to be doing there on the south edge of Sanders. So, after bolting back to my pack, I proceeded to jut out the thumb of my right hand while rolling up its four complementary opposable fingers into my palm as a single passenger car rapidly neared. Then, just as quickly, it passed me by without dropping so much as a single rpm.

“Hey,” I thought to myself, “I’m in the game. I am now officially a hitchhiker.” This feeling of accomplishment was slowly, but certainly, subdued and my elation abated when I came to the realization that I was suffering from a case of acute vehicular anemia; a simple self-diagnosis, based on the observation of the paucity in the flow of cars and trucks through this, the main artery connecting northeastern and southeastern Arizona.

And so began my first lesson in the waiting part of the hitchhike–the bum leg of a journey bumming rides. As with all hitchhikes, thumbers never knows how long the linger will last until they get that ride. But the ride instantaneously ends the wait. So, to paraphrase Yogi Berra, it’s only over when it’s over.

In over an hour, a total of a mere half-dozen cars, trucks, and motor homes managed to drain their way down through Sanders and drip past me and the waterless windmill at my back. This led me to wondering if, of all the roads I had crossed to get to that point of my 2,500-mile bus ride, this Route 666 may have been a dicey choice as a selection for my first-ever stab at flagging a ride. In the midst of pondering this question, vehicle number seven--a hitchhiker’s version of a VIN number--a well-worn blue-and-white pickup approached. As it did, I assumed the same position I had for the six that preceded it. Much to my expected surprise–one should always expect, but never assume the next car will stop--as I tracked the truck pass by, I noticed the color of the brake lights change from dull beet to bright red. As it rolled to an abrupt and gravelly stop half on and off the shoulder not fifty feet down, my eyes were immediately drawn away from the tailgate and to the back window in which a rifle lay cradled innocently in a gun rack. Transfixed by the sight and the implications that came with it, I groped for my gear as a flag as bright as a warning flare, itself as bright as the tail lights glaring back at me, shot up inside my head. Moving down the shoulder toward the truck, I passed by the proverbial flagman standing sentinel in the construction zone on the road to the rest of my life flashing his double-sided SLOW/STOP sign at me as I went by him. The message was as ambiguous to me as what I thought my next move should be.

“What on God’s more brown than green Earth do you think you’re about to do?” blurted a voice from within my head. Before I had a chance to decide whether the question was one I was willing to take a shot at answering, from in my head a whisper followed with a, "G-e-r-o-n-i-m-o?" as the passenger door swung open and a guy with short wavy hair, long reddish sideburns, cowboy boots, jeans, a tee-shirt with a cigarette pack cocooned in a sleeve, and a good five inches in stature and belt lengths on me spun out from the truck cab and looked me square in the eye. “Hop own e-in,” he offered in a pleasant, matter-of-fact, western twang. Fortunately for me, even though it was 1974, I had yet to see Easy Rider. Without that bias for reference, I found myself replying, “Hey, thanks!” in a sincere, yet tentative, tone that, along with the sound of the truck exhaust system, was apparently loud enough to drown out any reasoning voice coming from within. Lugging my things toward the rig, he directed me to throw them into the back. As I heaved my pack over the side and watched it slip into the already-cluttered truck bed, a split second of dread came over me thinking that maybe these guys are going to take off and leave me short on belongings. But they had no intentions of doing any such thing. Instead, the big guy offered me the seat in front in between him and the driver. This changed my feeling from dread to one of uneasiness. I had assumed I would get the seat by the door; but middle is what was offered and cowpoke sandwich it would be--no ranch on the side. I accepted it as graciously and as quickly as I could.

Ironically, there is this old riddle about cowboys and their pick-em-up trucks:

Q: If there are three guys riding down the road in the front seat of a pickup truck, how can you tell which one is the real cowboy?

A: The one in the middle, because he’s the only one who won’t have to get out to open the gate!

Climbing up and sliding into the seat, I exchanged a hello and a thanks for a howdy and a don’t mention it with the driver who was donning a big straw cowboy hat and sporting contrasting dark-lensed sun glasses which in turn contrasted a faint attempt at a blond mustache that had little contrast with his skin tone. Although sitting, he seemed to be more about my size and build than his buddy who was filling up much of the rest of the bench to my right. They both seemed to be about the same age and neither seemed much older than me. As the door slammed shut, and a with range of emotions swimming in my head and gut, the driver put the truck in gear and stepped heavy on the gas causing the right rear wheel to spin a rotation or two, from which a small dust cloud billowed, through which pebbles flew like buckshot. When all four tires gripped the road concurrently, we were on our way and I was officially bumming my first ride. Yeeee-haw!

As it was with the truck to the highway, it took us a bit to get our conversation into high gear and up to speed. Where I was going and where I was from broke the ice. The driver was more open to conversation than his friend to my right, who seemed more content to either listen or ignore. I couldn’t quite tell. He said they lived in southeastern Arizona and were on their way back home from Wyoming, where they had gone on a road trip for the weekend to visit some girls they knew there. I told him that it seemed like an awfully long way to go. But I wasn’t necessarily the best judge of such things. After all, it was a mere few hours earlier--although it felt like a world away--that I let a possible “roll around in ze’ hay,” with the West German chick in Albuquerque slip through my grasp for this unanticipated cruise through the desert with these couple of cowboys who drove maybe a thousand miles seeking a similar experience. Talk about the chances of finding a nail in a haystack. And as a result of our respective decisions, there we three sat looking through a bug-spattered windshield, streaking along a narrow line of jet-black pitch pressed thin atop a tan and yellow land.

The differences in our respective senses of distance was put in perspective when he mentioned that they thought nothing of driving ninety miles to go to a bar for a beer on a Friday night. To someone coming from somewhere where the population density was way more elbow-to-elbow than theirs, it seemed incredible that someone would want to have to go that far just to belly up and bend their own elbow. And to bring the vantage point home, he also told me something I really had a difficult time fathoming. That the town he lived in had been moved by the mining company who owned the land--as well as most of the locks, stocks, and barrels in eye sight and rifle shot--to a location a few miles away because it wanted to extract the ore from the ground beneath it. Cities just don’t move. A far as I was concerned, New York City was always where it was and was where it always would be. Apparently, such a process of up and moving stakes is not unheard of in small, isolated mining towns, however. Although I do not recall the name of the town or even if it was told me, it quite possibly is in the Miami-Globe mining area of central Arizona, the site of some of the largest open-pit copper mine in the world. If so, the pit probably expanded out to engulf this company town and, thus, necessitated its relocation. It must be bizarre to look over the pit and be able to point to the space where you grew up. Ah, the yin and the yang of life. Here I was, a kid whose hometown was famous for its concentration of man and of its man-made monoliths reaching polydactylously skyward, sitting between two western boys who came from a vacant land and one of the the grandest of anthropogenic gouges carved into the Earth. And there we were, only moments before unknown to each other, on a newly created piece of common human ground.

The longer we drove, the more comfortable I began to feel about the company and my circumstance. Validating this feeling, as we bantered, I happened to notice the key chain dangling from the ignition and spied, attached to it, an alligator clip coyly flashing a metallic smile my way through the jumble of keys with which it shared the ring, as if it were peering at me through a clump of reeds in a swamp. “These dudes must be cool enough,” I surmised to myself as I smiled knowingly back at that fingertip-saving appliance swaying there inches from my left knee. Not wanting to push my luck, however, I resisted the temptation of asking my new-found friends whether they possessed anything for that gator to sink its teeth into.

Road Running

So, there we were just tooling down the road engrossed in our own little cultural exchange, smoking cigarettes, and talking over the wind blowing though the cab about stuff like the county-fair rodeoing in which the driver would sometimes compete. “Geez. He really is a real cowboy,” I thought to myself. The rhythm of the conversation was abruptly broken when, all of a sudden and out of the azure, he jammed on the brakes, pulled off onto the shoulder, swung his right arm back over my head, and grabbed the rifle out of its rack as the pickup came to a blunt, dead stop. Anxiously curious as to what caused these actions and what his next ones might be, and if I had any direct involvement or participation in any of them, I manage to force a restrained stammer, “Uhhhh, what’s going on?” out through my teeth.

With no immediate response other than a click from the safety disengaging, an air of distracted agitation seemed to have come over the driver-turned-rifleman riding shot-gun in the driver’s seat. Sensing that he was shooting a piercing look out his open window, in a low, loathsome voice, all he said was, “Cah-yoats!” Leaning forward in my seat I was able to follow his line of sight about forty yards across the other side of the two-lane road and down into the piñon-juniper flat below to make out two motionless canid figures-- one sitting and the other standing motionlessly beside it. “Damn cah-yoats,” he repeated with the added expletive for emphasis as he drew his arm and the firearm up into the line of vision I had been sharing with him to bring the animals into the “V” of his sights. My initial reaction was one of conflicted, better-you-than-me-coyote relief.

I couldn’t tell if he first checked for passing cars, but I can only hope and assume so, because before I knew it, getting a bead on the coyotes, he constricted into a motionless hunch, squeezed on the trigger, and shot straight across the road. The crack radiating from the rifle was instantaneously followed by a puff of dust rising a foot or two from the paws of one of the pair of live targets. Without hesitation, the reclining coyote sprang up and the two bolted south and parallel to the road as the shooter bolt-actioned the spent shell from the chamber as the remaining round took its place. As he fired at the animals on a dead run a wonderfully pungent smell of combusted gunpowder permeated the cab. Angered, frustrated, and possibly embarrassed that the second bullet missed its mark as well, he threw the truck in gear, stomped down on the gas pedal, and with the rifle butt sitting in his lap and the barrel poking out the window, he peeled out after them. In the process, he reached down and groped around on the floor till he located a new box of bullets, which he stuck in his crotch, ripping the open the top with one hand. As he pulled out a couple of bullets, my concern was no longer that they may be intended for me, but that the driver was more concerned about loading them and tracking the location of his prey than he was about staying on the road they were fleeing beside. With that, I offered to hold the wheel with my left hand while he reloaded with his right; an offer he gladly accepted without hesitation and with an almost, “Oh, gee, I almost forgot that I was doing the driving,” tone in his response. So, never having driven a pickup before, I gripped the steering wheel and guided the truck somewhere mostly to the right of the center line and over a rise and some gentle bends in the road as I watched the speedometer needle cross past the 50 and then 60 and beyond. By this time, I had no idea where the coyotes had gone. My concentration was fixed on the task at hand, my hand was fixed to the wheel, and my eyes were darting inside my head which was moving every which way I thought necessary to keep all four tires fixed to the macadam while the driver had the rifle cradled in his arms fixing to load it. Now, I didn’t know that much about firearms--I had shot some .22s at the firing range in boy scout camp--but I knew enough to know that it was taking way longer than it should to load. When I saw that his motions were getting herkier and then jerkier and then saw him grimace and start to wrestle with it an curse at it, I knew there must be a problem.

“Damn new bullets,” he exclaimed, “they ain’t fittin' right and are jamming the damned thing,” acknowledging and conceding to himself and, I suppose to his friend and maybe even their guest, that this hunt was over. He did succeed in extracting the then misshapen shell before quickly dispatching the weapon to its rightful (rifle?) place back in the rack and flipping the box of ammo behind the seat in frustrated disgust. In doing so, he, to my relief, regained full control and operation of the vehicle, which gave me the opportunity to pry my death-gripping fingers from the wheel, flexing them and thereby restoring my white knuckles back to their normal pinkish brown.

Oh, Canidae

I then offered an ambivalently sympathetic, “Too bad!” I hope is was sincere ambivalence and not a duplicitous or patronizing comment. Like the windmill I took the time to observe only minutes before, I had never until that moment seen an actual coyote, be it in the wild or anywhere else, except on TV and in the movies. So, there was no cause for me to have acquired a hatred for them nor had anyone in my experience ever attempted to instill such feelings in me. Thus, without sharing the deep-seated animosity of my cowboy cohorts, I felt kind of city-slicker sorry for these somewhat comical critters. I was silently hoping they would pull off a successful getaway. But, to be a gracious guest, I didn’t want to let on about these feelings, nor was I compelled to enter into a philosophical debate on the rights of coyotes to be left alone versus their need, to an animal, to be exterminated. Besides, I don’t know if I was sure just what my philosophy was on the beasts. I just didn’t want to see them killed while they were just minding their own business, and to, like Wile E. with his Acme, Inc., shipments, and be left to their own devices (beep-beep!).

What I did do, though, was ask the driver why he was so bent on killing them, because the only thing I was sure about was that I sure was curious about the spectacle I had just witnessed and the act to which I had been something of an accomplice. And, what it was that triggered the whole incident. He proceeded to give me a quick lecture on the livelihood of the rancher, his read on livestock management, and on how the coyote--these range roaches, herd vermin, high-plains pick-pockets, baby beeves thieves, and hen-house hoodlums--does business and affects the cowboy and cattleman’s way of life. Things he’d learned in his first semester at the cow college of hard knocks. In his mind, the only good coyote was, well, you know the drill. All he was doing was his part in prairie pest control and a sort of twist to the adopt-a-highway program by orphaning coyote pups. It gives a new meaning to road kill, as well.

No regrets, Coyote

I just get off up aways

You just picked up a hitcher

A prisoner of the white lines on the freeway

--Coyote, Joni Mitchell, Hejira, (c) 1976

Reflecting back on the event, I wonder if his actions were part bravado in an effort to put on a good show for the turista from back east-ah or if this was simply another day in a cowboy cubicle in the wild west. Whatever his motive, it all seemed genuine to me. And I must say, a good show it was. The funny thing about all this is that is that on page 301 in Webster’s Ninth Collegiate Dictionary, there are illustrations of a cow and of a coyote, and directly cross-column from the definition of a cowboy is the one for coyote. Could there be much more of a connection to all of this than either of us could have know? What's for sure about this is that at least one thing between the two is a coworker!

Winner, winner...

Somewhere between returning to a semblance of normal driving decorum and the small town of St. Johns, our conversation turned from coyote sustenance to mine. I may have made mention of my calculating the possibility of getting stuck out in the desert and of the modest store of desert survival stash I was packing. I’m not sure. But for some reason, the guy riding shot gun--not the one that had just done the shooting to my left--asked me if I was hungry. I told him that I was OK; that I'd had breakfast back in Albuquerque. But that just did not sit well with him; not one ort of an iota. So as if not to be outdone by his buddy, he nonchalantly and without fanfare or hesitation proceeded to plant his feet to the floor, reach with both hands out the truck window, grab hold of the rain gutter curled above it, twist his torso windoward, push his head outside the cab, and pull himself up until he sat precariously with his butt half out of the truck. It was kind of like riding side-saddle at a mile a minute. With the wind blowing into his right-arm sleeve and his tee-shirt ballooning and collapsing in irregular undulations and fluttering and snapping against his body, the ashes and bits of partially burned rolling paper peeled away and were getting sucked into the air stream from the orange-glowing tip of the cigarette constricted in the downwind corner of his mouth. In contrast, the pack of Marlboros twisted up into his left short sleeve remained miraculously wrapped intact. Without even batting it, out the corner of his eye the driver looked past me at his friend teetering a mere false move away from becoming true roadside grit. He didn’t even bother to let up on the gas, as if this was a business-as-usual move on the part of his pard.

What all this had to do with whether I might be hungry was yet to become evident to me. Then, prying his left hand free from its rooftop perch, he reached his arm around back into the truck bed. For counterbalance, he sank his left foot between the seat cushion and back rest beside me. Resisting, for a host of reasons, an urge to hold onto pant leg of my host to help anchor him–grabbing his leg seemed way more trouble than steadying a steering wheel–this time I sat by as a bystander. Straining my spectating neck so I could look back through the rear window, I continued to watch to see just what kind of stunt this--what I was coming to realize was the second of a pair of whack-o buckaroo bookends I was wedged between--was attempting to pull off. Then, presto, he yanked up a big red-and-white bucket emblazoned with the words Kentucky Fried Chicken and sporting the likeness of The Colonel (this was back in the days when Harlan Sanders was still crowing about his birds and still hawking the only recipe there was: original, before it had to be so called). I’d heard of pulling a rabbit out of a hat, but chicken in a tub from thin air doing sixty in a pickup certainly was an original. Using his body as a windbreak, he then curled his arm around the container like a fullback with goal-to-go and maneuvered the bucket forward against the stiff resisting air, slipped it through the window, and passed it to me. Touchdown! Nice delivery. Then, without skipping a beat, he reached around a second time, and with a grappling-hook grasp, latched onto a six-pack of Coors Beer in cans. Swinging the at-the-time rare Golden cargo and then limboing himself back inside the truck, he dropped down into his seat, took a long, savoring last drag off what was left of his unevenly burned cigarette, and flicked the butt out the same window from which his had just been hanging out of. I guess it could have been considered a fast-food, drive-by, drive-in, take-out, drive-through, pick-up and delivery truck window. I’ve heard of chicken franks, but hot-dogging for some fried chicken? This may all just be another variation on why the chicken crossed the road. And maybe KFC really stands for “krazy cowpokes!?”

After downing a deep, cleansing breath-of-fresh-air chaser to his smoke-filled exhale, the stunt rider sat for a second gazing out through the windshield. He then turned to me and, with a friendly smile, barked, “Have ya’a beer,” as he ripped a pale-yellow can from its plastic ring holder and handed me one before doing the same to the driver and then taking one for himself. “Coors,” I thought to myself as prepared to crack open the can, “the mythical brew of The West!” Although I had heard of it, back in 1974 it was almost impossible to find this product of the Rocky Mountains east of the Pecos; not to mention the Mississippi or the Hudson. Something to do with the fact that it needed to be shipped refrigerated, or at least that was a large part of the myth. So, my beer was Rheingold, the dry beer. Whatever the reason Coors was out of reach, the word back east was that you knew you must be “out west” if you were drinking a Colorado-brewed Coors. And these Arizona boys saw fit to bestow one upon me. I was honored. It may sound silly, now, but at the time I was honored, nonetheless. After popping the top and toasting and drinking to the moment and one another, he coaxed, “Now, go on. Eat up!” as he looked down at the chicken bucket sitting unopened in my lap. Whether I had actually been hungry or not didn’t matter at that point. There was no way I could refuse the offer now, what with the performance I had just observed in his effort to get it to me. As it turned out, I must have been famished and began to wolf down the herbed and spiced poultry flesh like the proverbial coyote in a chicken coop we had just been discussing. And before I could finish one piece, I would hear, “Have ya’nother.” The same was the case when I was about to kill a beer. So, there I was, the impromptu guest-of-honor at a ride-beggar’s banquet thrown in spontaneous style by humble hosts with unfettered generosity. “Man, this is living,” I thought to myself then. And I still think so, now.

Ridin' High

After going through the map dot of St. Johns in a dash, we rode astride and against the flow of the Little Colorado River and began the gradual, almost imperceptible rise in elevation as the changes in ecosystems such ascents bring as we passed through the local hub of Springerville and into the foothills of the White Mountains and enter Apache-Sitgreaves National Forest on the way to Alpine. My driver mentioned that they had originally intended to turn off from Route 666 earlier–likely Springerville--but would drive about thirty miles out of their way to get me to my destination. Trying to convince them that it would be fine to let me off where it was convenient for them, that I didn’t want to be any more trouble than I already had been. But that was a fruitless argument. They would have nothing to do with such a notion. I got the feeling that they somehow felt responsible for my well-being and were going to see to it that I would get to where I was going to safe and sound--aforementioned shooting and food service stunts aside. That was all there was to it. End of discussion. Who were these guys, anyway? We never even exchanged first names.

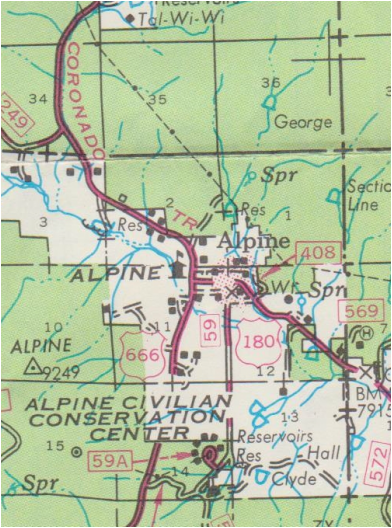

Not a quarter mile south of Alpine, Arizona--a small mountain community peeking through the evergreen-draped slopes common to the 8000-foot level of the region and a welcome relief from the baked, buff-hued flats of the Colorado Plateau below--we came upon what I was looking for. A sign nailed to a pine tree for the Aspen Lodge, which was listed in my “Where to Stay...” book as a youth hostel, led us down a dirt road to cluster of rustic-style log cabins, and which evidently is still there (http://aspenlodgealpine.com/). Apparently, primarily a mountain resort the Aspen Lodge doubled as a hostel for passers-by like me during slow times or off season when vacancies were plentiful.

Slightly buzzed from the beer and with a crop filled with Kentucky fried, my cowboy compadres, as promised, drove me right up to the door of the lodge office. I shook both their hands, poured out the passenger-side door, grabbed my gear out of the back, and went in to see if there was a place for me to bunk for the night. True to form, the pickup waited out front to make sure I had secured shelter for the night. After signaling to the affirmative, we exchanged waves, so-longs, and good lucks as they hung a tight U-ie, let out a collective cowboy yee-haa and, disappearing into the dust they had just churned up, faded from view and earshot and rode on to continue their lives. I can’t remember thanking those guys enough. I guess that’s because there was no way I possibly could.

The Rest of the Story...

That was it. That experience from Sanders to Alpine hooked me on hitchhiking and its trappings. One of the curious aspects of hitching I came to find out is that as soon as a given ride is over--especially a good one--you are once again alone and on your own to flag down the next ride. But that night I would sleep tight and out about wrestling with that aspect of thumbing in the morning, because I was, at that moment licking my fingers at the Aspen Lodge. And I was the more full in spirit--and body—for it.

My exploration into the exotic world of common ranching and farming equipment was abruptly curtailed by the growing hum of approaching southbound traffic. The sound brought me back to the reality of what it was I was supposed to be doing there on the south edge of Sanders. So, after bolting back to my pack, I proceeded to jut out the thumb of my right hand while rolling up its four complementary opposable fingers into my palm as a single passenger car rapidly neared. Then, just as quickly, it passed me by without dropping so much as a single rpm.

“Hey,” I thought to myself, “I’m in the game. I am now officially a hitchhiker.” This feeling of accomplishment was slowly, but certainly, subdued and my elation abated when I came to the realization that I was suffering from a case of acute vehicular anemia; a simple self-diagnosis, based on the observation of the paucity in the flow of cars and trucks through this, the main artery connecting northeastern and southeastern Arizona.

And so began my first lesson in the waiting part of the hitchhike–the bum leg of a journey bumming rides. As with all hitchhikes, thumbers never knows how long the linger will last until they get that ride. But the ride instantaneously ends the wait. So, to paraphrase Yogi Berra, it’s only over when it’s over.

In over an hour, a total of a mere half-dozen cars, trucks, and motor homes managed to drain their way down through Sanders and drip past me and the waterless windmill at my back. This led me to wondering if, of all the roads I had crossed to get to that point of my 2,500-mile bus ride, this Route 666 may have been a dicey choice as a selection for my first-ever stab at flagging a ride. In the midst of pondering this question, vehicle number seven--a hitchhiker’s version of a VIN number--a well-worn blue-and-white pickup approached. As it did, I assumed the same position I had for the six that preceded it. Much to my expected surprise–one should always expect, but never assume the next car will stop--as I tracked the truck pass by, I noticed the color of the brake lights change from dull beet to bright red. As it rolled to an abrupt and gravelly stop half on and off the shoulder not fifty feet down, my eyes were immediately drawn away from the tailgate and to the back window in which a rifle lay cradled innocently in a gun rack. Transfixed by the sight and the implications that came with it, I groped for my gear as a flag as bright as a warning flare, itself as bright as the tail lights glaring back at me, shot up inside my head. Moving down the shoulder toward the truck, I passed by the proverbial flagman standing sentinel in the construction zone on the road to the rest of my life flashing his double-sided SLOW/STOP sign at me as I went by him. The message was as ambiguous to me as what I thought my next move should be.

“What on God’s more brown than green Earth do you think you’re about to do?” blurted a voice from within my head. Before I had a chance to decide whether the question was one I was willing to take a shot at answering, from in my head a whisper followed with a, "G-e-r-o-n-i-m-o?" as the passenger door swung open and a guy with short wavy hair, long reddish sideburns, cowboy boots, jeans, a tee-shirt with a cigarette pack cocooned in a sleeve, and a good five inches in stature and belt lengths on me spun out from the truck cab and looked me square in the eye. “Hop own e-in,” he offered in a pleasant, matter-of-fact, western twang. Fortunately for me, even though it was 1974, I had yet to see Easy Rider. Without that bias for reference, I found myself replying, “Hey, thanks!” in a sincere, yet tentative, tone that, along with the sound of the truck exhaust system, was apparently loud enough to drown out any reasoning voice coming from within. Lugging my things toward the rig, he directed me to throw them into the back. As I heaved my pack over the side and watched it slip into the already-cluttered truck bed, a split second of dread came over me thinking that maybe these guys are going to take off and leave me short on belongings. But they had no intentions of doing any such thing. Instead, the big guy offered me the seat in front in between him and the driver. This changed my feeling from dread to one of uneasiness. I had assumed I would get the seat by the door; but middle is what was offered and cowpoke sandwich it would be--no ranch on the side. I accepted it as graciously and as quickly as I could.

Ironically, there is this old riddle about cowboys and their pick-em-up trucks:

Q: If there are three guys riding down the road in the front seat of a pickup truck, how can you tell which one is the real cowboy?

A: The one in the middle, because he’s the only one who won’t have to get out to open the gate!

Climbing up and sliding into the seat, I exchanged a hello and a thanks for a howdy and a don’t mention it with the driver who was donning a big straw cowboy hat and sporting contrasting dark-lensed sun glasses which in turn contrasted a faint attempt at a blond mustache that had little contrast with his skin tone. Although sitting, he seemed to be more about my size and build than his buddy who was filling up much of the rest of the bench to my right. They both seemed to be about the same age and neither seemed much older than me. As the door slammed shut, and a with range of emotions swimming in my head and gut, the driver put the truck in gear and stepped heavy on the gas causing the right rear wheel to spin a rotation or two, from which a small dust cloud billowed, through which pebbles flew like buckshot. When all four tires gripped the road concurrently, we were on our way and I was officially bumming my first ride. Yeeee-haw!

As it was with the truck to the highway, it took us a bit to get our conversation into high gear and up to speed. Where I was going and where I was from broke the ice. The driver was more open to conversation than his friend to my right, who seemed more content to either listen or ignore. I couldn’t quite tell. He said they lived in southeastern Arizona and were on their way back home from Wyoming, where they had gone on a road trip for the weekend to visit some girls they knew there. I told him that it seemed like an awfully long way to go. But I wasn’t necessarily the best judge of such things. After all, it was a mere few hours earlier--although it felt like a world away--that I let a possible “roll around in ze’ hay,” with the West German chick in Albuquerque slip through my grasp for this unanticipated cruise through the desert with these couple of cowboys who drove maybe a thousand miles seeking a similar experience. Talk about the chances of finding a nail in a haystack. And as a result of our respective decisions, there we three sat looking through a bug-spattered windshield, streaking along a narrow line of jet-black pitch pressed thin atop a tan and yellow land.

The differences in our respective senses of distance was put in perspective when he mentioned that they thought nothing of driving ninety miles to go to a bar for a beer on a Friday night. To someone coming from somewhere where the population density was way more elbow-to-elbow than theirs, it seemed incredible that someone would want to have to go that far just to belly up and bend their own elbow. And to bring the vantage point home, he also told me something I really had a difficult time fathoming. That the town he lived in had been moved by the mining company who owned the land--as well as most of the locks, stocks, and barrels in eye sight and rifle shot--to a location a few miles away because it wanted to extract the ore from the ground beneath it. Cities just don’t move. A far as I was concerned, New York City was always where it was and was where it always would be. Apparently, such a process of up and moving stakes is not unheard of in small, isolated mining towns, however. Although I do not recall the name of the town or even if it was told me, it quite possibly is in the Miami-Globe mining area of central Arizona, the site of some of the largest open-pit copper mine in the world. If so, the pit probably expanded out to engulf this company town and, thus, necessitated its relocation. It must be bizarre to look over the pit and be able to point to the space where you grew up. Ah, the yin and the yang of life. Here I was, a kid whose hometown was famous for its concentration of man and of its man-made monoliths reaching polydactylously skyward, sitting between two western boys who came from a vacant land and one of the the grandest of anthropogenic gouges carved into the Earth. And there we were, only moments before unknown to each other, on a newly created piece of common human ground.

The longer we drove, the more comfortable I began to feel about the company and my circumstance. Validating this feeling, as we bantered, I happened to notice the key chain dangling from the ignition and spied, attached to it, an alligator clip coyly flashing a metallic smile my way through the jumble of keys with which it shared the ring, as if it were peering at me through a clump of reeds in a swamp. “These dudes must be cool enough,” I surmised to myself as I smiled knowingly back at that fingertip-saving appliance swaying there inches from my left knee. Not wanting to push my luck, however, I resisted the temptation of asking my new-found friends whether they possessed anything for that gator to sink its teeth into.

Road Running

So, there we were just tooling down the road engrossed in our own little cultural exchange, smoking cigarettes, and talking over the wind blowing though the cab about stuff like the county-fair rodeoing in which the driver would sometimes compete. “Geez. He really is a real cowboy,” I thought to myself. The rhythm of the conversation was abruptly broken when, all of a sudden and out of the azure, he jammed on the brakes, pulled off onto the shoulder, swung his right arm back over my head, and grabbed the rifle out of its rack as the pickup came to a blunt, dead stop. Anxiously curious as to what caused these actions and what his next ones might be, and if I had any direct involvement or participation in any of them, I manage to force a restrained stammer, “Uhhhh, what’s going on?” out through my teeth.

With no immediate response other than a click from the safety disengaging, an air of distracted agitation seemed to have come over the driver-turned-rifleman riding shot-gun in the driver’s seat. Sensing that he was shooting a piercing look out his open window, in a low, loathsome voice, all he said was, “Cah-yoats!” Leaning forward in my seat I was able to follow his line of sight about forty yards across the other side of the two-lane road and down into the piñon-juniper flat below to make out two motionless canid figures-- one sitting and the other standing motionlessly beside it. “Damn cah-yoats,” he repeated with the added expletive for emphasis as he drew his arm and the firearm up into the line of vision I had been sharing with him to bring the animals into the “V” of his sights. My initial reaction was one of conflicted, better-you-than-me-coyote relief.

I couldn’t tell if he first checked for passing cars, but I can only hope and assume so, because before I knew it, getting a bead on the coyotes, he constricted into a motionless hunch, squeezed on the trigger, and shot straight across the road. The crack radiating from the rifle was instantaneously followed by a puff of dust rising a foot or two from the paws of one of the pair of live targets. Without hesitation, the reclining coyote sprang up and the two bolted south and parallel to the road as the shooter bolt-actioned the spent shell from the chamber as the remaining round took its place. As he fired at the animals on a dead run a wonderfully pungent smell of combusted gunpowder permeated the cab. Angered, frustrated, and possibly embarrassed that the second bullet missed its mark as well, he threw the truck in gear, stomped down on the gas pedal, and with the rifle butt sitting in his lap and the barrel poking out the window, he peeled out after them. In the process, he reached down and groped around on the floor till he located a new box of bullets, which he stuck in his crotch, ripping the open the top with one hand. As he pulled out a couple of bullets, my concern was no longer that they may be intended for me, but that the driver was more concerned about loading them and tracking the location of his prey than he was about staying on the road they were fleeing beside. With that, I offered to hold the wheel with my left hand while he reloaded with his right; an offer he gladly accepted without hesitation and with an almost, “Oh, gee, I almost forgot that I was doing the driving,” tone in his response. So, never having driven a pickup before, I gripped the steering wheel and guided the truck somewhere mostly to the right of the center line and over a rise and some gentle bends in the road as I watched the speedometer needle cross past the 50 and then 60 and beyond. By this time, I had no idea where the coyotes had gone. My concentration was fixed on the task at hand, my hand was fixed to the wheel, and my eyes were darting inside my head which was moving every which way I thought necessary to keep all four tires fixed to the macadam while the driver had the rifle cradled in his arms fixing to load it. Now, I didn’t know that much about firearms--I had shot some .22s at the firing range in boy scout camp--but I knew enough to know that it was taking way longer than it should to load. When I saw that his motions were getting herkier and then jerkier and then saw him grimace and start to wrestle with it an curse at it, I knew there must be a problem.

“Damn new bullets,” he exclaimed, “they ain’t fittin' right and are jamming the damned thing,” acknowledging and conceding to himself and, I suppose to his friend and maybe even their guest, that this hunt was over. He did succeed in extracting the then misshapen shell before quickly dispatching the weapon to its rightful (rifle?) place back in the rack and flipping the box of ammo behind the seat in frustrated disgust. In doing so, he, to my relief, regained full control and operation of the vehicle, which gave me the opportunity to pry my death-gripping fingers from the wheel, flexing them and thereby restoring my white knuckles back to their normal pinkish brown.

Oh, Canidae

I then offered an ambivalently sympathetic, “Too bad!” I hope is was sincere ambivalence and not a duplicitous or patronizing comment. Like the windmill I took the time to observe only minutes before, I had never until that moment seen an actual coyote, be it in the wild or anywhere else, except on TV and in the movies. So, there was no cause for me to have acquired a hatred for them nor had anyone in my experience ever attempted to instill such feelings in me. Thus, without sharing the deep-seated animosity of my cowboy cohorts, I felt kind of city-slicker sorry for these somewhat comical critters. I was silently hoping they would pull off a successful getaway. But, to be a gracious guest, I didn’t want to let on about these feelings, nor was I compelled to enter into a philosophical debate on the rights of coyotes to be left alone versus their need, to an animal, to be exterminated. Besides, I don’t know if I was sure just what my philosophy was on the beasts. I just didn’t want to see them killed while they were just minding their own business, and to, like Wile E. with his Acme, Inc., shipments, and be left to their own devices (beep-beep!).

What I did do, though, was ask the driver why he was so bent on killing them, because the only thing I was sure about was that I sure was curious about the spectacle I had just witnessed and the act to which I had been something of an accomplice. And, what it was that triggered the whole incident. He proceeded to give me a quick lecture on the livelihood of the rancher, his read on livestock management, and on how the coyote--these range roaches, herd vermin, high-plains pick-pockets, baby beeves thieves, and hen-house hoodlums--does business and affects the cowboy and cattleman’s way of life. Things he’d learned in his first semester at the cow college of hard knocks. In his mind, the only good coyote was, well, you know the drill. All he was doing was his part in prairie pest control and a sort of twist to the adopt-a-highway program by orphaning coyote pups. It gives a new meaning to road kill, as well.

No regrets, Coyote

I just get off up aways

You just picked up a hitcher

A prisoner of the white lines on the freeway

--Coyote, Joni Mitchell, Hejira, (c) 1976

Reflecting back on the event, I wonder if his actions were part bravado in an effort to put on a good show for the turista from back east-ah or if this was simply another day in a cowboy cubicle in the wild west. Whatever his motive, it all seemed genuine to me. And I must say, a good show it was. The funny thing about all this is that is that on page 301 in Webster’s Ninth Collegiate Dictionary, there are illustrations of a cow and of a coyote, and directly cross-column from the definition of a cowboy is the one for coyote. Could there be much more of a connection to all of this than either of us could have know? What's for sure about this is that at least one thing between the two is a coworker!

Winner, winner...

Somewhere between returning to a semblance of normal driving decorum and the small town of St. Johns, our conversation turned from coyote sustenance to mine. I may have made mention of my calculating the possibility of getting stuck out in the desert and of the modest store of desert survival stash I was packing. I’m not sure. But for some reason, the guy riding shot gun--not the one that had just done the shooting to my left--asked me if I was hungry. I told him that I was OK; that I'd had breakfast back in Albuquerque. But that just did not sit well with him; not one ort of an iota. So as if not to be outdone by his buddy, he nonchalantly and without fanfare or hesitation proceeded to plant his feet to the floor, reach with both hands out the truck window, grab hold of the rain gutter curled above it, twist his torso windoward, push his head outside the cab, and pull himself up until he sat precariously with his butt half out of the truck. It was kind of like riding side-saddle at a mile a minute. With the wind blowing into his right-arm sleeve and his tee-shirt ballooning and collapsing in irregular undulations and fluttering and snapping against his body, the ashes and bits of partially burned rolling paper peeled away and were getting sucked into the air stream from the orange-glowing tip of the cigarette constricted in the downwind corner of his mouth. In contrast, the pack of Marlboros twisted up into his left short sleeve remained miraculously wrapped intact. Without even batting it, out the corner of his eye the driver looked past me at his friend teetering a mere false move away from becoming true roadside grit. He didn’t even bother to let up on the gas, as if this was a business-as-usual move on the part of his pard.

What all this had to do with whether I might be hungry was yet to become evident to me. Then, prying his left hand free from its rooftop perch, he reached his arm around back into the truck bed. For counterbalance, he sank his left foot between the seat cushion and back rest beside me. Resisting, for a host of reasons, an urge to hold onto pant leg of my host to help anchor him–grabbing his leg seemed way more trouble than steadying a steering wheel–this time I sat by as a bystander. Straining my spectating neck so I could look back through the rear window, I continued to watch to see just what kind of stunt this--what I was coming to realize was the second of a pair of whack-o buckaroo bookends I was wedged between--was attempting to pull off. Then, presto, he yanked up a big red-and-white bucket emblazoned with the words Kentucky Fried Chicken and sporting the likeness of The Colonel (this was back in the days when Harlan Sanders was still crowing about his birds and still hawking the only recipe there was: original, before it had to be so called). I’d heard of pulling a rabbit out of a hat, but chicken in a tub from thin air doing sixty in a pickup certainly was an original. Using his body as a windbreak, he then curled his arm around the container like a fullback with goal-to-go and maneuvered the bucket forward against the stiff resisting air, slipped it through the window, and passed it to me. Touchdown! Nice delivery. Then, without skipping a beat, he reached around a second time, and with a grappling-hook grasp, latched onto a six-pack of Coors Beer in cans. Swinging the at-the-time rare Golden cargo and then limboing himself back inside the truck, he dropped down into his seat, took a long, savoring last drag off what was left of his unevenly burned cigarette, and flicked the butt out the same window from which his had just been hanging out of. I guess it could have been considered a fast-food, drive-by, drive-in, take-out, drive-through, pick-up and delivery truck window. I’ve heard of chicken franks, but hot-dogging for some fried chicken? This may all just be another variation on why the chicken crossed the road. And maybe KFC really stands for “krazy cowpokes!?”

After downing a deep, cleansing breath-of-fresh-air chaser to his smoke-filled exhale, the stunt rider sat for a second gazing out through the windshield. He then turned to me and, with a friendly smile, barked, “Have ya’a beer,” as he ripped a pale-yellow can from its plastic ring holder and handed me one before doing the same to the driver and then taking one for himself. “Coors,” I thought to myself as prepared to crack open the can, “the mythical brew of The West!” Although I had heard of it, back in 1974 it was almost impossible to find this product of the Rocky Mountains east of the Pecos; not to mention the Mississippi or the Hudson. Something to do with the fact that it needed to be shipped refrigerated, or at least that was a large part of the myth. So, my beer was Rheingold, the dry beer. Whatever the reason Coors was out of reach, the word back east was that you knew you must be “out west” if you were drinking a Colorado-brewed Coors. And these Arizona boys saw fit to bestow one upon me. I was honored. It may sound silly, now, but at the time I was honored, nonetheless. After popping the top and toasting and drinking to the moment and one another, he coaxed, “Now, go on. Eat up!” as he looked down at the chicken bucket sitting unopened in my lap. Whether I had actually been hungry or not didn’t matter at that point. There was no way I could refuse the offer now, what with the performance I had just observed in his effort to get it to me. As it turned out, I must have been famished and began to wolf down the herbed and spiced poultry flesh like the proverbial coyote in a chicken coop we had just been discussing. And before I could finish one piece, I would hear, “Have ya’nother.” The same was the case when I was about to kill a beer. So, there I was, the impromptu guest-of-honor at a ride-beggar’s banquet thrown in spontaneous style by humble hosts with unfettered generosity. “Man, this is living,” I thought to myself then. And I still think so, now.

Ridin' High

After going through the map dot of St. Johns in a dash, we rode astride and against the flow of the Little Colorado River and began the gradual, almost imperceptible rise in elevation as the changes in ecosystems such ascents bring as we passed through the local hub of Springerville and into the foothills of the White Mountains and enter Apache-Sitgreaves National Forest on the way to Alpine. My driver mentioned that they had originally intended to turn off from Route 666 earlier–likely Springerville--but would drive about thirty miles out of their way to get me to my destination. Trying to convince them that it would be fine to let me off where it was convenient for them, that I didn’t want to be any more trouble than I already had been. But that was a fruitless argument. They would have nothing to do with such a notion. I got the feeling that they somehow felt responsible for my well-being and were going to see to it that I would get to where I was going to safe and sound--aforementioned shooting and food service stunts aside. That was all there was to it. End of discussion. Who were these guys, anyway? We never even exchanged first names.

Not a quarter mile south of Alpine, Arizona--a small mountain community peeking through the evergreen-draped slopes common to the 8000-foot level of the region and a welcome relief from the baked, buff-hued flats of the Colorado Plateau below--we came upon what I was looking for. A sign nailed to a pine tree for the Aspen Lodge, which was listed in my “Where to Stay...” book as a youth hostel, led us down a dirt road to cluster of rustic-style log cabins, and which evidently is still there (http://aspenlodgealpine.com/). Apparently, primarily a mountain resort the Aspen Lodge doubled as a hostel for passers-by like me during slow times or off season when vacancies were plentiful.

Slightly buzzed from the beer and with a crop filled with Kentucky fried, my cowboy compadres, as promised, drove me right up to the door of the lodge office. I shook both their hands, poured out the passenger-side door, grabbed my gear out of the back, and went in to see if there was a place for me to bunk for the night. True to form, the pickup waited out front to make sure I had secured shelter for the night. After signaling to the affirmative, we exchanged waves, so-longs, and good lucks as they hung a tight U-ie, let out a collective cowboy yee-haa and, disappearing into the dust they had just churned up, faded from view and earshot and rode on to continue their lives. I can’t remember thanking those guys enough. I guess that’s because there was no way I possibly could.

The Rest of the Story...

That was it. That experience from Sanders to Alpine hooked me on hitchhiking and its trappings. One of the curious aspects of hitching I came to find out is that as soon as a given ride is over--especially a good one--you are once again alone and on your own to flag down the next ride. But that night I would sleep tight and out about wrestling with that aspect of thumbing in the morning, because I was, at that moment licking my fingers at the Aspen Lodge. And I was the more full in spirit--and body—for it.